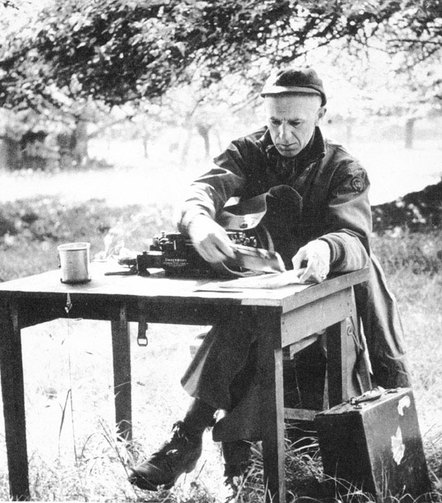

Image is from her book, The Edge of the War Zone.

Mildred Aldrich, an elderly American expatriate in France, arose each morning at dawn during the summer of 1914, wrapped herself in a cloak, and went to her lawn to gaze over the French countryside. Each morning the sun illuminated the same lovely valley: “miles and miles of laughing country, little white towns just smiling in the early light, a thin strip of river here and there, dimpling and dancing, stretches of fields of all colors.”

For years Aldrich had lived in Paris as a theater critic for the New York Times. But age and declining health had changed her. She moved to the country to find “a quiet refuge” and “the simple life.” In retirement Aldrich liked to look over the countryside as she worked in her garden. Winding through the fields and villages, the Marne River made a “wonderful loop” to within a mile of her hilltop house. Aldrich’s American friends chided her for abandoning her native land, but even while cherishing the French countryside, she had not forgotten the United States. She reported: “I turn my eyes to the west often with a queer sort of amazed pride.” The United States was, however, a country for “the young, the energetic, and the ambitious.” Aldrich had once been all of those, but now she cherished the calm life of rural France.

Image from The Edge of the War Zone

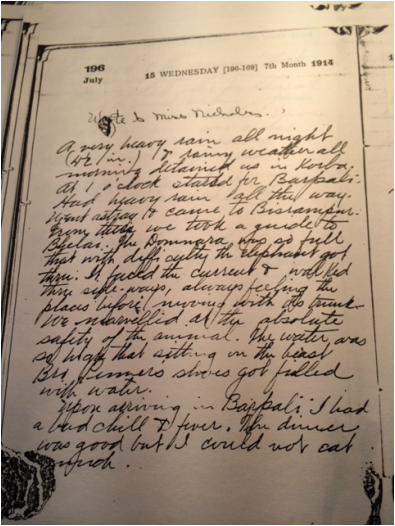

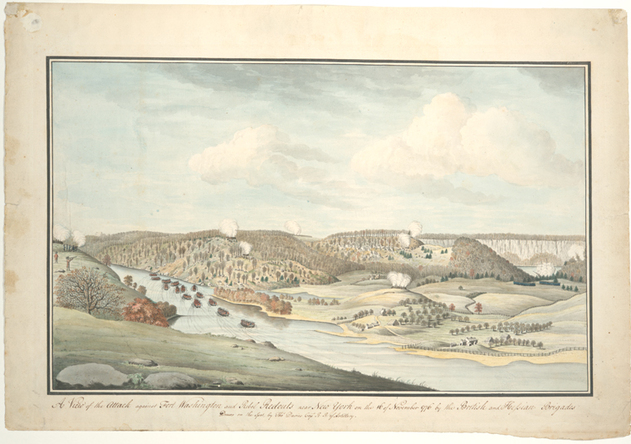

If Mildred Aldrich had been an active political reporter rather than a retired drama critic, she might have sensed that the assassination in Sarajevo would not be so easily forgotten. Within a few weeks there were a series of threats, first by Austria against Serbia, then by Russia against Austria, then by the other major powers of Europe, including England and France, against each other. These threats, once acted upon, would drive Europe into World War I. And the first great battle of that war would soon take place along the Marne River, in the very countryside that Mildred Aldrich viewed with such serenity from her front yard.

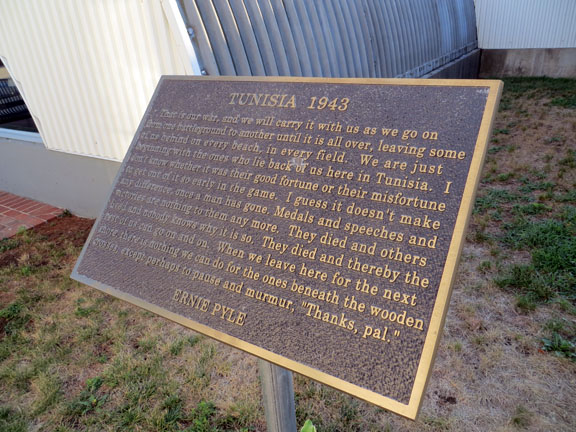

“It will be the bloodiest affair the world has ever seen...."

A few weeks after her first mention of Sarajevo, Aldrich was writing home, “It is a nasty outlook. We are simply holding our breaths here.” On July 30, 1914, she envisioned the looming combat: “It will be the bloodiest affair the world has ever seen—a war in the air, a war under the sea as well as on it, and carried out with the most effective manslaughtering machines ever used in battle.”

A few days later a man walked up and down the road near her farmhouse beating a drum. He posted an announcement on a door at a neighbor's farm, and the village women along with Mildred Aldrich ran to read it. A "cold chill" ran down her spine when she saw that it was an order for mobilization. War had not yet been declared, but with armies mobilizing all across Europe she reasoned correctly that there would be no turning back.

On August 3, 1914, she wrote: "Well—war is declared. I passed a rather restless night. I fancy every one in France did. All night I heard a murmur of voices, such an unusual thing here. It simply meant that the town was awake and, the night being warm, every one was out of doors."

Photo by Bill Youngs, 1986

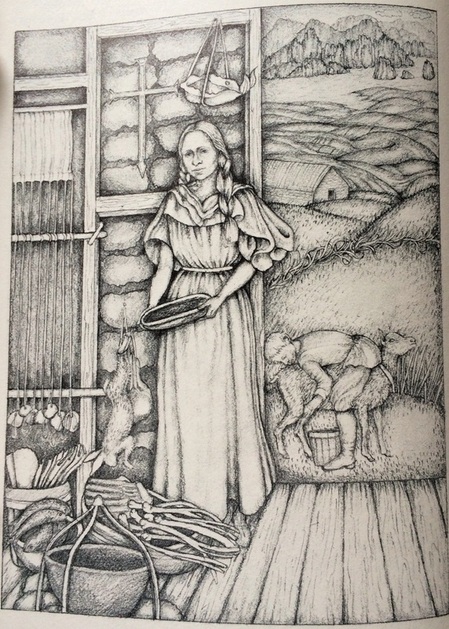

Mildred Aldrich was old enough to remember having seen men marching through the streets of Boston on their way to the Civil War about a half century before. Back then, "crowds of stay-at- homes, throngs of women and children lined the sidewalks, shouting deliriously, and waving handkerchiefs, inspired by the marching soldiers." Somehow things were different in France in 1914: " no marching soldiers, no flying flags, no bands of music. It is the rising up of a Nation as one man—all classes shoulder to shoulder, with but one idea—'Lift up your hearts, and long live France.'" Aldrich was deeply stirred by the site of men going to war, and of the women and children they left behind....

Day after day I have watched the men and their families pass silently, and an hour later have seen the women come back leading the children. One day I went to Couilly to see if it was yet possible for me to get to Paris. I happened to be in the station when a train was going out. Nothing goes over the line yet but men joining their regiments. They were packed in like sardines. There were no uniforms— just a crowd of men—men in blouses, men in patched jackets, well-dressed men—no distinction of class; and on the platform the women and children they were leaving.... As the crowded train began to move, bare heads were thrust out of windows, hats were waved, and a great shout of "Vive la France" was answered by piping children's voices, and the choked voices of women—"Vive l'Armee"; and when the train was out of sight the women took the children by the hand, and quietly climbed the hill.

Ever since the 4th of August all our crossroads have been guarded, all our railway gates closed, and also guarded—guarded by men whose only sign of being soldiers is a cap and a gun, men in blouses with a mobilization badge on their left arms, often in patched trousers and sabots, with stern faces and determined eyes, and one thought—"The country is in danger."

The men that Mildred Aldrich knew in her tiny village went off to war with a mixture of patriotism and resignation. One came by her house before leaving and told her:

"Well, if I have the luck to come back—so much the better. If I don't, that will be all right. You can put a placque down below in the cemetery with 'Godot, Georges: Died for the country '; and when my boys grow up they can say to their comrades, 'Papa, you know, he died on the battlefield.' It will be a sort of distinction I am not likely to earn for them any other way."

A few weeks from now this blogger will travel to France to be in the Marne region on the one hundredth anniversary of the great battle that stopped the German advance toward Paris. In the mean time, I am planning to read and reread Mildred Aldrich's vivid a account of the opening of the war as experienced on her "hilltop on the Marne."

(You know you want to!)

If you enjoyed this article on World War I, you might also enjoy these entries:

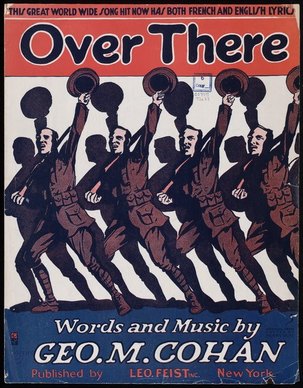

• "Over There": World War I Veterans Sing Songs of the Great War, 67 Years Later

• Memories of the Lafayette Escadrille at the American Cathedral in Paris

• The Outbreak of the Great War, My Grandfather's Diary, and an Elephant Ride

RSS Feed

RSS Feed