During the next five years Elliott and Eleanor's mother, Anna, would both die.

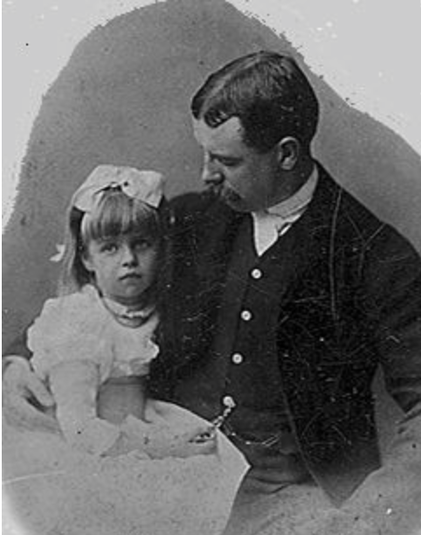

Source: Wikipedia Commons

Elliott spent much of the summer in bed and found solace in medicines more poisonous than the hurt ankle: morphine and laudanum. These drugs, prescribed freely in Victorian America, carried Elliott into a pleasant oblivion where neither the pain of the ankle nor the mortification of his personal failures could touch him. During the summer and fall of 1889 his ankle slowly healed, but his drug dependence increased. Anna begged him to give up narcotics. He refused, and in December he abruptly left the family and went south, ostensibly to seek a rest cure.

Anna, left at home with Eleanor and baby Ellie, was disconsolate. She hoped Elliott would return one afternoon shortly after Christmas, and when he did not she went to her room, lay on the bed, and sobbed. In the evening she wrote Elliott beseeching him to come home and be well. Sentence by sentence she drew a picture of a bereaved household. She and Eleanor had opened Christmas presents alone. She had gone by herself to a holiday party, but was so "wretched" she came home after a few minutes.

Whenever the postman came Eleanor rushed down the stairs hoping for word of her father. Anna told Elliott, "I do nothing but think of you and pray you will come back. . . . I am so terribly lonely without you." "Dearest," she wrote, "Throw your horrid cocktails away and don't touch anything hard .... Remember that your little wife and children love you so tenderly and will try to help you in every possible way they can to conquer in the hard hard fight." The "hard fight" - self-discipline was what Elliott needed. "Nell," she said, "it must be an entire conquest, a partial one is no good. "

There, she had done her wifely duty; she had preached the doctrine of self-control. But she could not end on such an austere note; she was a wife, not a schoolmistress, and she needed him. "Don't leave us again," she implored, "We can't do without you."

The adults of Abington could hardly object to their children's devotion to Elliott, for they too were captivated by him. He drank apple cider at their firesides, read them his favorite poems, and invited them to his rooms to sing songs around the piano. During the winters when snow lay deep on the hillsides around Abington, Elliott organized sledding parties for the whole town. He joined the local Episcopal Church, sang in its choir, and was soon made a member of its vestry. Like his father, "Greatheart," Elliott became known for his charities. He distributed old clothes and Christmas turkeys to the poor and persuaded his brother-in-law to support missions in the coal-mining camps on his lands. One of Elliott's many admirers was so taken by him that in 1900 she urged her friends to vote for the Republican ticket simply because Teddy Roosevelt, the Vice-Presidential candidate, was Elliott's brother.

Elliott Roosevelt was probably never more respected and loved than during his stay in Abingdon. But he was privately tormented by the absence of his wife and children. Surely he had shown himself worthy to be forgiven. If only he might return some day to his apartment and find Anna waiting for him, her beautiful face glowing with love and understanding, her arms ready to enclose him in an embrace of reconciliation.

After her mother's death Eleanor and the boys went to live with their Grandmother Hall on 37th Street. Elliott wanted the children with him in Virginia, but in her will Anna requested that they be raised by Mary Hall, and none of their relatives would encourage Elliott to assume custody. He returned alone to Abingdon after the funeral, but Mary, moved by compassion, invited him to spend Christmas with the children.

The house on 37th Street, which had been filled with roses and lilies nine years before for Anna and Elliott's wedding, now held a beautifully decorated Christmas tree illuminated by candles. In the late afternoon on the day before Christmas Eleanor and her father, along with her brothers, aunts, uncles, and grandmother sat down to their dinner of roast turkey. In the evening they sang carols. Anna's sister Pussie played the piano while Elliott led the singing with his good strong voice. Eleanor particularly remembered,

"Silent night, holy night,

All is calm, all is bright..."

That night two stockings hung at the foot of Eleanor's bed, one from Grandmother Hall and one from her father. The next morning she found grandmother's stocking full of "utilitarian gifts" a toothbrush, soap, a washcloth, pencils, and a pencil sharpener. In the other stocking her father had "put in little things a girl could wear - a pair of white gloves, a pretty handkerchief, several hair ribbons, and a little gold pin." Beneath the Christmas tree was another present, a fox terrier puppy bred by her father in Virginia. He gave it, she believed, "because he knew I would love to have something to care for and call my own." She, in turn, had made her father a handkerchief case and a tobacco pouch.

After breakfast the servants came into the living room and received their presents. Then the family went to a Christmas service at Calvary Church, where Elliott and Anna had been married. Eleanor nestled beside her father, and he held his prayer book so that she could read it with him. Anna had stood with Elliott long ago at the front of this church; now she was gone, but their daughter was with him....

(You know you want to!)

This current post is one of a growing number of historically-themed entries on americanrealities.com. To see a complete list of other entries, click here

If you liked this post on Eleanor Roosevelt, you may also enjoy these other ER posts:

-- Eleanor Roosevelt Tours the South Pacific During World War II

-- Eleanor Roosevelt, Lorena Hickok, a Buick Roadster, and a Trip to Quebec

-- Happy Birthday to Eleanor Roosevelt -- October 11, 2013

-- Eleanor Roosevelt and Advertisements -- Tacky or Thoughtful

RSS Feed

RSS Feed