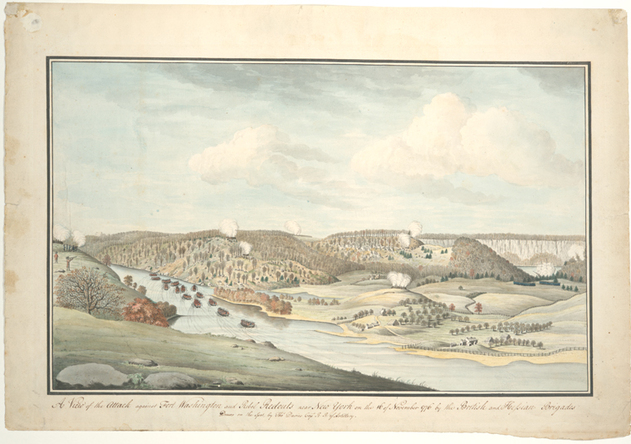

Fort Washington, the last American stronghold on Manhattan, was on a high cliff over the Hudson, surrounded on all but the river side by the British. Washington believed that the position was indefensible but was persuaded by his subordinate, Nathanael Greene, that it could be held. On November 16 he watched in despair from the opposite shore as his fears were realized. The outerworks of the fort were too extensive to be held by the 2,800 men left in Manhattan. They were easily overwhelmed, and the defenders retreated into the fort itself. But it was small and impossibly crowded, and at the day’s end the situation was hopeless, and the garrison surrendered. It was the worst defeat of Washington’s career. In addition to losing almost three thousand men, he lost guns, cannon, munitions, and supplies.

Source: Wikipedia Commons, New York Public Library

David Hackett Fischer in Washington's Crossing says of the general, "As the full weight of the disaster fell upon him, he turned away from his lieutenants and began to weep 'with the tenderness of a child.'"

David McCullough in his book 1776 concurs that the fall of Fort Washington was a bitter blow: "In a disastrous campaign for New York" the fort's surrender was "the most devastating blow of all, an utter catastrophe." But he doubts the general's tears: "Washington is said to have wept," McCullough writes, "as he watched the tragedy unfold from across the river, and though this seems unlikely given his well-documented imperturbability, he surely wept within his soul."

In comparison to the great problems in American history, such as measuring the social impact of the American revolution, the question of whether Washington wept at this defeat is hardly fundamental. And yet this is no trivial subject, for it leads to deeper understanding of Washington's personality, and by extension it provides insights into the way a leader's emotional make-up contributes to the character of his leadership. Additionally, examining the question provides an interesting exercise in historical inquiry. I'll begin with the answer, and then provide the evidence.

The answer: George Washington did weep, both inwardly and outwardly, at the fall of Fort Washington.

I base this conclusion on two kinds of evidence: (1) other information we have on George Washington's personality, and (2) further information about the actual circumstances that brought the general to tears.

Washington's Emotional Personality

Washington was famed, as McCullough notes, for his "imperturbability." He could exude confidence when others despaired. As he became more successful in war, his fame for coolheadedness grew. But along the way his emotions were often in evidence, whether in disappointment, triumph, anger, or empathy. A few weeks before the fall of Fort Washington, the general watched his army melt away in a pell-mell retreat before a British attack at Kip's Bay on Manhattan. Was he Imperturbable in this moment? Hardly! Here is a description of that moment from "The Continental Army in the Year of Independence":

Again and again Washington tried to rally the troops who surged past him. Finally he came upon two brigades, less terrified than the others, and stationed them behind a stone wall to oppose a British advance. But as soon as a handful of the enemy appeared, these also fled. Now Washington completely lost control of himself. Throwing his hat on the ground and lashing out with his riding crop at men and officers, he cursed and exclaimed: “Are these the men with whom I am to defend America? Good God! Have I got such troops as these?” But the men continued to run, and Washington slumped in his saddle, exhausted from anger and despair. His aides stayed by their chief, watching anxiously as the last of the soldiers made their escape. Across the field, some fifty British soldiers came toward the paralyzed leader. Washington was too hurt to care what happened. Finally, the aides, realizing that they must act, took his bridle and led their dazed commander to safety.

Years later when Washington had won the war, and the time came to give up his command of the army at an ceremony before the Continental Congress at Annapolis, he revealed again his capacity for deep emotion. Here is how Robert Middlekauff describes that event in The Glorious Cause, his epic account of the American Revolution:

Washington rose, bowed to Congress, who uncovered but did not bow. He then read his speech in a manner that, according to contemporary observers, brought tears to many eyes. Washington himself felt deep emotion—his hand holding the speech trembled throughout, and when he spoke of his aides, those dear members of his military "family," he gripped the paper with both hands. His deepest feeling, however, was reserved for an even finer moment—when, commending "the Interests of our dearest Country to the protection of Almighty God, and those who have the superintendence of them, to his holy keeping," he faltered and was almost unable to continue.

The noble horse of Gen. Washington stood with his breast pressed close against the end of the west rail of the bridge, and the firm, composed, and majestic countenance of the General inspired confidence and assurance in a moment so important and critical. In this passage across the bridge it was my fortune to be next the west rail, and arriving at the end of the bridge rail, I was pressed against the shoulder of the general's horse and in contact with the general's boot. The horse stood as firm as the rider, and seemed to understand he was not to quit his post and station.

(Quoted in Fischer, Washington's Crossing)

There came a man alone to us having on a surtout [long overcoat], as we conjectured (it being exceeding dark), and inquired for the engineers. We now began to be a little jealous for our safety, being alone and without arms, and within 40 rods of the British trenches. The stranger inquired what troops we were, talked familiarly with us a few minutes, when being informed which way the officers had gone, he went off in the same direction, after strictly charging us, in case we should be taken prisoners, not to discover to the enemy what troops we were. We were obliged to him for his kind advice, but we considered ourselves as standing in no great need of it; for we knew as well as he did that Sappers and Miners were allowed no quarters, at least are entitled to none by the laws of warfare, and of course should take care, if taken and the enemy did not find us out, not to betray our own secret.

In a short time the engineers returned and the afore-mentioned stranger with them. They discoursed together some time when, by the officers often calling him "Your Excellency," we discovered that it was General Washington.

(Quotation is from James Kirby Martin's edition of the diary, Ordinary Courage.)

The Commander-in-Chief's Objective Circumstances Fort Washington

All of these markers of George Washington's personality, show a man who felt deeply about the course of the war and cared deeply, personally about the men who served under him. But what of the circumstances of Fort Washington? What might have increased the likelihood that he shed tears as the fort surrendered?

We know that Washington had been beaten repeatedly during the past few weeks. We know that the fall of the fort that bore his name was a bitter blow to the Revolution. But what else? The battle he watched was in the distance. None of the soldiers at Fort Washington rubbed against the general's boot as they crossed a bridge; none spoke with him in the trenches in the night; none was as close as those thirty yards that separated the general from the British at Princeton.

In other words, all that fighting in the distance might well remained something of an abstraction for this man who was most engaged in events were intimate, where suffering or triumph or simple fortitude was close and personal.

Well, perhaps so, except for one little detail that brings all of the others into focus -- so to speak.

As Fort Washington fell, George Washington was watching the battle through a telescope.

And so he saw in agonizing detail individual soldiers felled by bayonet and bullet. The scene was so proximate that he was almost there among them -- and yet, he could do nothing for them.

And so, my friends, in his despair George Washington did indeed turn away from that heart-rending scene and weep -- "with the tenderness of a child."

View more entries on the American Realities blog...

(You know you want to!)

This current post is one of a growing number of historically-themed entries on americanrealities.com. To see a complete list of other entries, click here

RSS Feed

RSS Feed