The First Euro-Americans: Norsemen in the New World

J. William T. Youngs

Viking Ships, Drawing by Cecily Moon

For thousands of years the peoples of America and Europe lived in separate worlds, as remote from one another as distant stars. Europeans came to America slowly, groping at the edges of the New World, touching the shores long before they penetrated the interior. Columbus sailed across the Atlantic four times but never realized he had reached new continents. England sent an explorer, Sebastian Cabot, to America in 1497, but established no permanent settlements for more than a century. There were, however, European settlements in the “New World” long before the voyages of Columbus and Cabot. One thousand years ago Norsemen colonized Greenland, on the fringe of North America. There they clung for almost five centuries, building farms and churches, trading with Europe, sending parties to the mainland. Their history shows in microcosm many elements of American history: a European culture being adapted to conditions in the New World, contacts between North America and Europe, and the hardships and rewards of the colonist’s life.

Roughly a thousand years ago Europeans from Norway began settling Greenland, a rugged island on the edge of the New World. Their early contacts with North America did not lead to massive immigration by other Europeans; the distinction of starting that movement was left to Christopher Columbus. But the Norsemen did establish dozens of communities in this remote land, communities where life was as intense and varied as in any European town. Few records survive from these early societies, but we know enough to recognize that the story of the Norse settlements is one of the most interesting chapters in the history of European contact with America and anticipates, in some ways, the later history of European colonization. In order to understand this unique society, we will review the five centuries of Norse experience in Greenland, but let us first try to imagine the reality of these distant times by picturing a day in the settlements.

The year is 1150 A.D. In a small Greenland farmhouse a Norse family is beginning the day. The father, first to rise, leaves his bed of skins and steps to the firepit in the center of the room. Taking embers from a small hole beside the pit, he lights the fire. Although the room is chilly, he makes only a small blaze, for wood is precious in Greenland. To light the windowless room he touches a flaming twig to the seal oil in a small soapstone lamp.

His wife is now awake, nursing their four-month-old infant; she hears the other children beginning to stir. The father goes outside to check the late spring weather and is pleased with what he sees. Above the mountains the sun is just rising. Looking down over green sloping fields to the calm fiord below, he notices a few small patches of fog, but otherwise the air is clear. It will be a warm day.

From where he stands he can see green pastures, farmhouses, and a stone church. In the water perhaps a mile away a neighbor is heading out to sea to fish from a small wood boat. He hears the sea gulls’ piercing cries and a bell sounding matins in the cathedral a few miles away. From the great manor at Brattahlid, where Eric the Red once lived, he can hear the sharp ring of a blacksmith’s hammer.

Along the west coast of Greenland for several hundred miles are farmsteads like his own where other Norsemen are beginning the day. Some will go to the fields; some will fish or hunt along the shore. Directly across the open sea on the Labrador coast, some three days’ sail to the west, Norsemen are felling trees to replenish Greenland’s scant supply.

Returning to the house, the man finds that his wife has finished preparing the morning meal. His two-year-old son is playing with a chess piece; he takes it away, for the child may lose it on the earthen floor. The child starts to cry, but his older sister calms him by pressing in his hands a simple wood doll. Breakfast is a broth made from reindeer meat, a little bread, and some cheese. After breakfast the man goes outside again, his oldest son with him. During the day his wife will stay near the house with the children. She will Weave the wool from their sheep into fine cloth for their best clothes and for export to Iceland and Norway. Later, when the children become restless, she will take them into the fields behind the house and gather berries.

Meanwhile, the father and eldest son take their bows and arrows, and leading a packhorse Walk into the mountains along a glittering brook that splashes past their house. If they are lucky they will shoot arctic hares or even a reindeer, which will be slung on horseback. If the hunt is not successful, the horse will carry back hay from the upper pastures. They will also look for livestock - cattle, sheep, or goats - that may have wandered too far from the house.

In such activities as these, early Norsemen spent their years in Greenland. Settled on a great island that almost touches present-day Canada in the north, voyaging occasionally to the shores of the North American continent, hunting animals more American than European in origin, they may be regarded as the first European colonists in the New World. They lived in Greenland for some five centuries, longer than Europeans have been in America since Columbus came in I492. And yet we know little about them.

The story of the Norse settlers begins and ends in mystery. We do not know why they came to America; we do not know what happened to them when their settlements were abandoned in the fifteenth century; and we know little about their five hundred years in Greenland. The Greenlanders did not leave the letters, diaries, and civil records historians must rely on to reconstruct the past. In fact, no written documents whatsoever survive from the Norse settlements. Fortunately, the settlers did leave other kinds of records. First are the sagas, tales told by generation after generation of Norsemen around fires in Greenland and Iceland and eventually written down. These tell us something about such people as Leif Ericson and Eric the Red. Then there are Icelandic and European sources - histories, annals, religious and trade records. But these few accounts are frequently inaccurate.

We have another kind of evidence, however. Even when people do not consciously record their lives for posterity, they do create objects scholars can study. During their lifetime they leave walls, churches, dwellings, remnants of tools and toys, fragments of furniture. When they die, their skeletons are left in the ground, clothed in costume of their day.

Studying these and other sources, archaeologists and historians have pieced together a picture of Norse settlement in the West. Their researches have been incredibly diverse. In assembling a history of the world's climate they have tried to learn what happened to the Greenlanders. They have used linguistic analysis and studies of local vegetation to determine what parts of America Leif Ericson visited. Radioactivity remaining in carbon from firepits indicates the age of settlements; animal bones furnish information about the Norse diet; and Eskimo legends suggest what happened to the settlers.

Even these sources, however, are constantly reevaluated. For many years "Vinland," the site of Leif Ericson’s colony in America, was thought to have been in New England because grapes (from which the name Vinland comes) are found no farther north. But then it appeared that berries along the coast of Canada were sometimes called grapes and made into wine. Some scholars believed that bones of the Norse settlers show symptoms demonstrating that the Greenlanders’ health was deteriorating in the later years of settlement; others disagree. A saga thought to be historically accurate today is supplanted tomorrow.

The historical record is complicated still more by the obscuring litter of forgeries. It is exciting to believe that the Vikings reached not only Newfoundland but also Rhode Island or Minnesota or Oklahoma. “Viking artifacts" have been found in all these places. For many years a tower in Rhode Island was claimed to have been built by Vikings, though it was easily proved that the construction was finished about I675. Minnesota's Kensington Rune Stone, unearthed in the late 1805, convinced many that Norsemen had reached the Midwest long before Columbus arrived in America. Subsequently, the stone proved to have been written much later than the date at which it was supposedly composed.

Studying these early men raises frustrating problems, but Norse research is so complex that it is remarkable how much we do know. The Vikings may not have reached Oklahoma or even Minnesota, but they did leave clear marks of their history in Greenland and Newfoundland. Their story begins far from the shores of North America, for the first Viking adventures were European exploits. The Vikings’ ancestors had migrated to Scandinavia in ancient times. The Norsemen, inhabitants of modern Norway, lived on the fiords in small villages separated by mountains from the next cluster of settlements. The people farmed and grazed their livestock along steep mountain slopes and fished in the coastal Waters.

In the early days the typical Norseman did not travel more than a few miles from his birthplace. His world was his fiord and perhaps the fjord next to it. But late in the eighth century Scandinavians began exploring and raiding hundreds, even thousands of miles from their homes. The word “Viking,” which means sea rover, warrior, or pirate, began to be applied to them. The first known Viking raid landed three ships in Wessex, now a part of England, in about 787 A.D. Seven years later Vikings attacked and robbed the great British monastery at Jarrow, a center of European culture. During the next two centuries they conquered large sections of England, Scotland, Ireland, France, and Russia.

Historians have not yet fully explained this sudden change in the Scandinavian activities but find several probable factors. Famine and overpopulation may have incited some Norsemen to find new homes, and the ease with which Vikings could pillage other lands made raiding an attractive occupation. Accustomed to sea travel, they had the best fleets in Europe. Their ships were fast and maneuvered well. Driven by one sail and as many as thirty-two oarsmen, they could easily travel across the North Sea and up the great rivers into the heart of Europe. Vikings were also great warriors, and they were armed with axes, spears, swords, and javelins. Protected by chain-mail shirts, they usually fought together in a wedge formation. Although they did not carry livestock on raids, they frequently “horsed themselves" - stole mounts from those they attacked. All in all, they were much better warriors than their opponents, easily overwhelming the isolated monasteries that dotted the European countryside. As their strength grew, they were able to assemble large fleets and conquer whole nations as well as great cities.

Once it was apparent that adventure and wealth were to be had on these expeditions, going "aviking” became almost a national pastime. Historians describe Viking expeditions as the chief national industry of the Scandinavian countries between 800 and 11OO. The Viking character easily met the new opportunities and challenges. “Viking fury" was a common description. Vikings who attacked enemy troops single-handedly, as if in an enraged trance, were called berserkers. In one story a Viking insists that his friends tie him to a tree when a "fury" comes over him because he does not wish to harm them. At this period a new plea was added to many European prayers: “From the fury of the Vikings, O God, deliver us."

Viking love of exploration and conquest brought the first Norsemen to America. The same movement that planted Vikings in Normandy and Russia later peopled Iceland, Greenland, and Vinland. But the Vikings did not come to America from Europe in one nonstop voyage. Columbus crossed the unknown seas between the Azores and the West Indies in one two-thousand-mile voyage, but Vikings crossed the North Atlantic in relatively short hops. In the ninth century Viking ships raided and occupied Britain, Ireland, and two groups of islands north of Britain, the Orkneys and the Shetlands. From there only a few hundred miles separated them from the Faroe Islands. A few hundred more miles took them to Iceland, the same to Greenland, and finally another few hundred to Newfoundland.

But how did they find their way across the wild North Atlantic to these obscure places? Probably their “discoveries” and settlements were preceded by an accidental sighting in each new region. Ships were frequently blown off course, and in the crystal-clear air blowing from the Arctic they might have been able to see mountainous land more than a hundred miles across open seas. The Irish may have told the Vikings about the islands. In the seventh and eighth centuries Irish monks traveling in crude skin boats had settled religious communities in the Faeroes and Iceland. (These monks deserted Iceland when the Vikings arrived, and some may have gone on to America.)

The Vikings first visited Iceland in 860 and began to colonize after 874. Some of the settlers may have been Norse noblemen fleeing the rule of Harold Fairhair, who conquered all Norway at this time. Others were Norse refugees expelled from Ireland in the early 900s.

Unrest and conflict so disturbed early Iceland that in 930 a movement spread for “law and order. " An althing, or legislature, was created, studied Norse laws, and adopted a legal code for Iceland. All free land-owners could take part in the althing's annual proceedings. It is the oldest extant legislative body in the world.

Through the next four centuries, from 900 to 1300, Iceland continued to grow. In the eleventh century its population may have reached seventy to eighty thousand. The settlers prospered by farming and fishing and by trading with Europe. Then in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries catastrophes afflicted the Icelanders: colder weather, the bubonic plague, volcanic eruptions, pirate raids, and unfavorable trading conditions in Europe. The plague alone may have killed half the population. Although the island was left poorer and less populous, the Norse Icelandic settlements have survived until today.

For more than a century Iceland was westernmost in the loosely associated Viking Empire, but farther to the west lay another, much larger island, soon named Greenland. Because climate and terrain formed the basis of the history of its people, we must pause to imagine Greenland a thousand years ago, shortly before the first European settlers arrived.

Greenland is the largest island on earth, approximately three times the size of France. Much of it lies north of the Arctic Circle; its northernmost point, Cape Morris Jessup, is only 440 miles from the North Pole. Almost 90 percent of the country is covered by a great ice cap, the world’s second-largest glacier. This great mass of ice reaches elevations often thousand feet and lies as deep as five thousand feet below the surface of the water. The cap is almost perfectly smooth, completely hiding the mountains and valleys underneath. The glacier has been built up over thousands of years by falling snows, which accumulate on the surface and never melt. It is massive but not inert. Ever building weight at the top pushes down, forcing the ice outward. At the edge of the seacoast the ice may travel as much as one hundred feet in a day, forcing its way into the water and breaking off with a thunderous cascade that can raise great waves and send shocks that kill fish for miles around. The glacial wind worsens the harsh climate of Greenland, sweeping over its icy surface, down the mountains, and out to sea; such is the wind’s omnipresence that Admiral Perry, the great nineteenth-century explorer, compared it to water flowing down a slope.

The ice cap is Greenland’s most impressive geological feature, but there is another Greenland more hospitable to human life. Between ocean and mountains are many grass-covered valleys, intersected by deep fjords. In places, particularly on the southwest coast, the land is rich in flora and fauna. Meadows filled with flowers, wild berries, birch, willow, alder, and mountain ash lie beside the fiords. The animal life has diminished over the centuries; a thousand years ago the valleys and coastal waters were full of reindeer, arctic hare, codfish, seals, and whales.

Eskimos have lived in Greenland for thousands of years, but the first recorded European contact was Eric the Red's voyage of about 981. Eric, banished from Iceland for killing a man in a feud, might have gone back to Norway but decided to go west instead. We do not know why he made that choice, but he or other Norsemen had once been driven off course and seen the mountainous shores to the west. It is little more than two hundred miles from northern Iceland to Greenland; one can see one island from the other.

Yet it was a courageous voyage that Eric undertook. His vessel, like that of the other westward explorers, was probably a knarr, not one of the Viking raiding ships we associate with Leif Ericson. A trading vessel, the knarr was a broader ship than its sea-raiding cousin. It did not have the dragons or other figures at bow and stern that embellished combat ships. An ancient knarr was recently unearthed near Roskilde Fjord, Denmark. Reasonably well preserved, it helps us imagine what Eric’s ship probably looked like. The restored vessel is fifty-four feet long and fifteen feet wide. Its keel and ribs are of oak, and its sides are pine planks caulked with twisted animal hair soaked in pine tar. The ships that sailed the Greenland waters a thousand years ago may have been slightly larger than this vessel and could have held thirty to seventy-five tons of cargo. They were open except for planking over the bow and stern sections for shelter from the elements. Carrying thirty or more people, they were propelled by a large square sail assisted by several sets of oars. The passengers sheltered in fur sleeping bags, which were also used to store their possessions.

In stormy weather with rain or snow falling on the boat and waves bursting over the sides, the vessels must have been hard to live in. There were no pumps and no decking, so that water had to be bailed to keep the vessel afloat. But in good weather with a following wind it would have been easy to forget the storms. We know something about how Viking ships sailed from an 1893 account of a voyage across the North Atlantic in the Viking, a vessel modeled on the “Gokstad ship," unearthed a few years before. This was a faithful reproduction, even to having the planks below the waterline tied with plant roots to let the hull flex as it moved through the water. The captain, Marnus Anderson, described the ship’s progress sailing before the wind: "In the twilight the Northern Lights threw their fantastic, pale light across the ocean, while the Viking glided over the waves like a seagull. With much admiration we watched the graceful motion of the ship, and with great pride we noted its speed, which from time to time was as high as eleven knots."

Eric the Red left no log, but we can reconstruct his voyage from our knowledge of Norse sailing and from oral accounts of his trip that were later written down. Sailing west from Iceland, he would have been in open sea for several days. His crewmen, like those of Columbus five hundred years later, must have wondered if they would ever see land again, but Norse experience hinted that there was always more land to the west. With fair winds they could see the mountains of Greenland after only two or three days of sailing. Once across the open waters, they worked their way along the Greenland coast looking for good land, arriving finally near present-day Julienhaab. There fertile fields and mountainous fiords were like parts of Iceland and Norway.

It was probably in this region that Eric spent the next three years, his term of banishment. In 985 he returned to Iceland where he told the story of the new land. He was eager to persuade other Icelanders to come and settle with him perhaps he wanted the prestige of leading a great migration, or perhaps he simply wanted Norse company. He was plainly hoping to promote settlement when he gave the region the appealing if somewhat misleading name of Greenland.

Eric managed to find several hundred Icelanders willing to accompany him to the new country. At the time the good land in Iceland was rapidly being filled. The sagas relate that Eric set out with a fleet of twenty-five boats, fourteen of which reached Greenland. Some may have sunk in the ocean, and others may have returned to Iceland. Once at sea it was not difficult for the Norsemen to find their way back to Greenland. Although they did not have the compass or the astrolabe, which later navigators used to find their way at sea, they could determine longitude and direction by sun and stars and thus repeat the course of Eric’s earlier voyage.

In Greenland the passengers scattered among the fiords looking for homesites. Eric set up his estate in Brattahlid, in one of Greenland’s best pasturelands. His home was near the middle of a hundred-mile line of Farmsteads, known as the Western Settlement. Other colonists went farther north to farm in an area later known as the Eastern Settlement. In the years that followed, hundreds of other Norsemen came to Greenland. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries the settlers numbered three to five thousand. Of these men and women, some went on to America.

Our first knowledge of the voyagers who went farther west is in the sagas. There are several versions, but the story of Norsemen in America appears consistently. In one of the sagas a man named Bjarni Herjulfson is the first to see America. A trader who carries goods between Norway and Iceland, he returns home to Iceland one winter and learns that his father has moved on to Greenland. Setting out to find him, Bjarni becomes lost. He sights land several times but refuses to stop because the country does not fit the description of Greenland, and he wants to get home. Another account has Leif Ericson, son of Eric the Red, blown off course and making the initial accidental discovery of America. In both versions, Leif makes the first settlement in the new land.

About 1002 A.D. Leif sets out with thirty-five men. He persuades his father to join him, but on the way to the boat Eric the Red falls and injures himself and must stay in Greenland. Leif then sails across the Davis Strait to the shores of North America. Continuing down the coast, he reaches a place abounding in grass, game, and salmon. Here the explorers carry their sleeping robes ashore and put up shelters. It is a fine, fertile land. A fish-rich stream runs through a meadow near the camp. There is plenty of timber to provide a cargo for the return trip, and one of the party even finds wild grapes. Leif and his men spend the winter there and return to Greenland in the next year. In subsequent years successive expeditions to America are led, in turn, by two of Leif ‘s brothers and a sister. They explore other parts of the coast, but they apparently prefer his original settlement.

For centuries people have wondered where Leif ’s American settlement was. The description of the grapes suggested a location somewhere in New England, but until 1960 no remnant of Viking settlements had been found anywhere west of Greenland. Then Helge Ingstad, a Norwegian archaeologist, found ruins in Newfoundland that appeared to be the remains of the much-sought-after Viking settlement. For several summers he and a team of other archaeologists carefully dug through the site at a place called L'Anse aux Meadows. He found nine dwellings with firepits on the Norse pattern, a primitive smithy, scraps of iron, a stone anvil, and a Norse spindle whorl, used in spinning wool. These were clear indications of a Viking settlement. Moreover, the configuration of land and sea the meadows, streams, fish, and coastline followed the description in the sagas. Nearby they even found berries from which wine could be made. If Eric could make “Greenland” out of patches of meadow below an ice cap, certainly Leif could have made “Vinland" (Wineland) of a place with these berries.

In the years ahead other Norse finds may be made in North America. It is sure that many wood-gathering expeditions went to the Labrador forests after Leif 's time, and other temporary settlements might have appeared. The location of Leif ’s colony has almost certainly been established Samuel Eliot Morison wrote, “We believe Ingstad has it."

Now we have indisputable proof that the Vikings reached America. Both their ability to reach Greenland and their presence on the brim of the American continent for five centuries would make it strange if they had not reached America. The surprise is that they did not settle more extensively. Certainly Newfoundland and the land to the south is more hospitable than Greenland. The Indians whom the Vikings encountered in America were hostile, but surely the Norsemen, who had conquered large sections of Europe and had better weapons than the Indians, could have carved out colonies in America if they had wished to do so.

They did not create lasting settlements in Newfoundland and New England simply because they did not need to. They had found good places to live in Greenland, which was itself the outpost of an outpost. Overcrowding in Europe had instigated the migration to Iceland. Over-crowding in Iceland, in turn, had encouraged migration to Greenland. If tens of thousands of Norwegians and Icelanders had sought homes in Greenland, some of them might have gone on to establish permanent settlements in America. But they did not; there was land enough in Greenland.

And so it was on the fjords of Greenland, not the hillsides of New England, that the first European colonists in the New World established their homes. Let us examine their history. Greenland, we must recall, was not a short-lived colony. During the centuries of Norse colonization the earliest settlers had children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren through ten generations and more. In that time they developed a distinctive culture, combining European and New World influences.

First we have the houses. Faced with winter temperatures of 40 degrees below zero, even on the seacoast, and with strong winds common, the settlers had to build dwellings that would be warm and solid. The early houses were chiefly great halls or main rooms, which served for living, eating, and sleeping. They were made with thick earthen walls and roofs of timbers, sod, and rocks. A central firepit provided warmth, light, and cooking.

These early halls resembled the dwellings of Iceland and Norway, but over the years a new pattern was formed. The large halls, probably too cold and drafty, came to be divided into smaller rooms. At first the great hall was split into two or three rooms. Late in the thirteenth century the “centralized farm” became common. These were large complexes encompassing from fifteen hundred to six thousand square feet and sometimes included rooms for animals. The precious cattle were placed at the very center of the structures.

Heat was provided by thick walls and furs and by modest fires. Probably the settlers spent most of the coldest days wrapped in robes, huddled together, fingers too chilled to spin wool or carve soapstone implements. The driftwood that was almost their only fuel can hardly have been plentiful enough to allow large fires every day. In especially cold times they must have been driven to cut scrub brush growing nearby, though it was needed to keep the winds from ripping away the pastureland. At times, winter isolation might be broken by a visit of neighbors, and in celebration a large fire and huge meal would be prepared. It was around such fires that tales were told that matured into the great Norse sagas. Then the guests would leave, and the family would be left alone in the wind and cold through the long dark winter.

Clothing, too, was influenced by the Greenland environment. Norse graveyards show us that the people sometimes dressed in the hooded, ankle-length woolen gowns worn in Norway. We know the settlements lasted well into the 1400s, because skeletons have been found clad in hooded capes and caps that were worn in Paris and Burgundy late in the fifteenth century. But one wonders if the Norse farmer wore a costume like that to tend the cows or his wife spun and cooked in her woolen gown. The day—to—day costume was more often made from the skins of deer, seals, or cattle. Sealskin trousers and heavy double fur coats were popular.

We know, then, that the Greenlander was well housed and well clothed. He also ate well, consuming the foods he took from the land and the sea. Goats and cattle provided milk that was processed into cheese in large tubs in rooms attached to the living quarters. For meat he ate mainly the flesh of birds, reindeer, and fish caught near the farm. In the summer there were wild berries in the fields nearby. The large number of grindstones found in their houses indicate that the Greenlanders had bread. Some historians contend that the grain must have been imported, but the settlers also grew some of their own and gathered wild grains from the fields and especially along the seashore.

Domestic animals weathered the North Atlantic passage along with their masters. The sheep were a particularly hardy breed, able to survive outside during the winter. The cattle were less sturdy and were housed for the winter either in stalls in the midst of human dwellings or in great long bytes or stables, whose thick earth walls faced south to absorb the sun's rays. Some doorways may have been filled with sod after the cattle were brought inside for the winter. Their manure was probably left in the stalls to provide extra insulation against the cold. Their feed was hay, carefully stored from the previous summer, and dried seaweed from the coast. Even so, the cows lost so much weight during the winter they must have looked like skeletons when they finally came out to pasture in the spring.

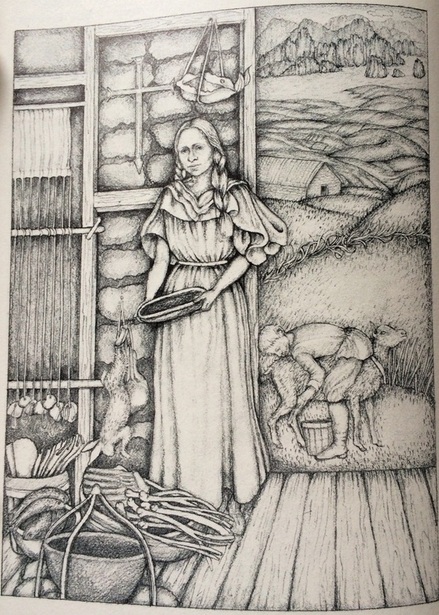

Norse Farmstead, Drawing by Cecily Moon

An animal broth was probably the staple in the Greenlander’s diet. People ate with large wood soup spoons; each had his own and carried it with him as a traveler today routinely takes his toothbrush along on a trip. After bones had been boiled into soup or gnawed through for their marrow, they were frequently thrown to the floor. Excavations show floors thickly littered with animal remains.

Making a living in Greenland meant performing a few essential tasks. The men spent their time on the farm in haymaking, herding, milking, and sheep shearing. They made implements from bones, including hoes and spades (from the bones of whales) and also buckles, knife handles, and even padlocks. They also made metal tools from local iron ore. Many of the larger farms had smithies where iron products were made and repaired, including axes, knives, scythes, sledgehammers, harpoons, fishing gear, arrowheads, and spears.

Men and women also spent time on finer crafts. Some carved walrus tusk ivory into fine chess pieces. The women spun and wove wool from the hardy sheep, creating textiles that found their way from Greenland’s fiords across the North Atlantic to Europe. Another necessary craft was carving of soapstone. The Greenland clay was not suitable for making pottery, and so the soft soapstone of the island was cut into bowls, spindle whorls or weights, oil lamps, and even large tubs holding up to forty quarts.

The average Greenlander probably spent most of his life near his own farm. But economic needs in the colonies took some Norsemen on long expeditions. The settlers were on hunting voyages far to the north where they killed walrus and narwhal. The walrus provided meat, ivory, and fur and the narwhal a spiral tusk that was marketed in Europe, sometimes as an alleged unicorn horn. The legendary unicorn was thought to have magical properties, and a powder ground from its “horn” was a popular apothecary item. The northern expeditions were frequent enough that parties were occasionally forced to winter far from the settlements, and Norsemen built at least one small church many miles north of the Arctic Circle. The Norsemen also sent expeditions to the coast of Labrador to gather timber and perhaps also to hunt black bear and sable for European trade. We do not know how often ships went to America. In time archaeologists may find artifacts left on the Labrador coast by such expeditions. They must have been common, because timber for houses, fires, and boats was in great demand in Greenland, and the three- or four-day voyage across the sea was relatively easy.

The hunt also took Norsemen on shorter expeditions down the fjords and along the coast. Seals were plentiful in most areas, and were valued for their skins and for their blubber, which could be boiled down into a fine oil for lamps and carried home in skin bags. On some expeditions the Norsemen must have traded with Eskimos, although such trade does not appear to have been an important part of their economy.

For several centuries trade was active between Greenland and Europe. The Norsemen probably imported some products, such as grain, honey, fine cloth, and tools. In turn, they exported many products. Besides woven fabric, walrus tusks, and narwhal horns, they shipped out the hides of walrus, seal, white and blue fox, and polar bear. They also exported some live animals. The Greenland white falcon was popular among European nobles and monarchs, such as Emperor Frederick II. On at least two occasions the Norsemen exported live polar bears; one went to a Norwegian king in appreciation for his appointment of a bishop for the Greenland church.

Norse trade kept the settlers in contact with Europe, and they appear to have traveled often between Greenland, Iceland, and Norway. Government, religion, friendship, and family ties united the far-flung settlements. One even learns of feuds begun in Iceland and concluded in Greenland. But for more than two and a half centuries Greenland was all but an independent country. Its laws were patterned loosely after those of Iceland and Norway. And like the Icelanders, the Greenlanders had an althing, a representative assembly that seems to have had both judicial and legislative functions. The althing at first was held at Brattahlid, ancestral seat of Eric the Red and Leif Ericson. Later it was moved a few miles south to Gardar near the Greenland cathedral. Outside Brattahlid archaeologists have found “booths,” small dwellings that were probably used as guesthouses by representatives attending the althing.

In the middle of the thirteenth century Norway asked Iceland and Greenland to acknowledge her jurisdiction, and in I261 after a long delay Greenland placed itself under the Norwegian crown. Thereafter the king had a representative in Greenland. Although Greenland records are lost, preventing close study of the representative's activities, at least we know he would have overseen the collection of taxes and the maintenance of civil peace. In practice, however, primary authority in the widely spread Norse communities was probably the local chief or the largest landowner.

During most of Greenland’s early history the Catholic church was much stronger than the Norwegian government. The first settlers had been pagans, worshipers of Thor, Wodin, and other Norse gods, but the sagas tell how Leif Ericson was converted to Christianity while spending a winter with the king of Norway. The king asked him to take the faith to Greenland, and on his return Leif brought along a priest. His father, Eric, was unwilling to abandon the old gods, but Leif quickly converted his mother, who built a small church at Brattahlid. For a time Eric’s wife left his bed, refusing to lie with a pagan. Perhaps to win back his wife, Eric converted to Christianity before his death in 1002.

The new faith grew rapidly in Greenland. Midway through the twelfth century the Western Settlement had four churches; the Eastern Settlement, twelve. In the early years the church suffered from the lack of a local bishop. Only a bishop could carry out many religious functions, such as consecrating bread and wine, confirmation, administering penance, and ordaining priests. Finally in 1124 the king of Norway appointed a bishop for Greenland. The first appointee regretted leaving friends and family far behind but agreed to go to the distant territory.

When the bishop arrived, the Greenlanders built him a cathedral. He was also given his own farm, which became the wealthiest in the land. His residence, at first a large farmhouse, was expanded with a ceremonial hall measuring fifty-five by twenty-five feet. The three firepits in the hall included one that covered more than fifty square feet. The church building, ninety by thirty feet, was built of stone and eventually had glass windows. It, too, was heated by three fires and even then was bitterly cold in the winter. Apparently the bishop was allowed to wear gloves while saying mass, a luxury not allowed ordinary priests. The church was dedicated to Saint Nicholas, patron saint of mariners, bakers, and children. On his feast day there would be a torchlight procession to the church and a special service in his honor. The bishop’s influence must have been great in medieval Greenland. His wealth was reflected by the presence on his farm of a byre that could hold more than a hundred cows. The bishop was responsible for collecting church taxes, the so-called Peter's pence, which went to Europe. Most of the Greenlanders paid in “kind,” the produce of their farms, and the bishop kept these products in storehouses in Gardar until they could be shipped to Europe. Thus, Greenland sealskins and walrus ivory found their way to Rome and helped pay for the Crusades and for struggles against heretics in Italy. The church now was so powerful that the parliament had been moved from Brattahlid to the great hall at Gardar. In this period two religious houses were also established in Greenland, a Benedictine convent in Sigluflord near a hot spring, and an Augustinian house in Kitisfiord.

These, then, are the outlines of life in the Greenland settlements. They were not mere colonial outposts like Raleigh's Roanoke, which lasted only a year or two, and yet the Norse settlements eventually did die out. Somewhere between I341 and I564 the Western Settlement was abandoned, and Greenland trade with Europe diminished. In the 1370s the last bishop who resided in Gardar died. Other bishops were appointed (the last did not die until I540), but none again went out to his post. The last recorded voyage from Norway to Greenland was in 1410. In the sixteenth century and later, when sailors from France, England, Spain, and the Netherlands reestablished ties with the New World, parties of explorers occasionally touched Greenland. Some reported seeing Norse ruins, but none found any Norsemen. What had happened?

In spite of the scant records, we can trace some causes of Greenland's decline. Perhaps the most important one was a climatic change in the fourteenth century; we know that about this time the weather became a good deal colder. Such a drop in temperature must have strained Greenland’s resources; more wood would be needed for heat, and the growing season would be shorter. It meant also that ice frequently blocked navigation to Europe. Trade was further inhibited by European conditions. Merchants in Bergen gained a monopoly on the Norwegian trade with the West and curtailed voyages to Greenland. The European market for walrus tusks also fell with an influx of elephant-tusk ivory from Africa. These may not have been the only problems. The bubonic plague, which ravaged Europe in the fourteenth century and struck Iceland and Norway in I549 and I 350, may well have reached Greenland also. In the late 1300s pirates began raiding Iceland and may have struck Greenland. Locusts and soil erosion could have damaged the crops; and deficiencies in food, brought about by the shorter growing season, may have caused malnutrition.

Let us return, then, to the one thing that is certain: early Norse culture in Greenland did disappear. Many historians believe that the end must have come tragically when a brave people finally succumbed, ravaged by disease, malnutrition, and isolation. Samuel Eliot Morison talks of the last survivors as “hardly able to find enough food to keep alive, staring their eyes out all through the short, bright summer for the ship from Norway that meant their salvation." Gwen Jones speaks of the “inexorable and heart-chilling doom" of the Norsemen.

It is not certain, however, that the ending was so tragic. After all, the Greenland settlements did not disappear overnight. Well over a century passed from the time the Western Settlement was abandoned to the death of the last Norseman in Greenland. The settlements died out, but individual settlers were not necessarily helpless. They might well have chosen their own fates. As the climate deteriorated, many must have decided to go elsewhere. The plague that struck Iceland made land available on that somewhat more hospitable island. The Norse population probably declined steadily during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. From several thousand it probably dwindled to several hundred. Of these, some must have decided to stay in the dying settlements; others probably continued the movement back to Iceland; and quite possibly still others merged their lives with the natives of Canada or Greenland, who were now better able to survive than the Norsemen.

We know that assimilation into native populations was a Norse trait. The early Vikings who settled in Russia and France soon became more Russian or French than Scandinavian. As the climate grew colder the Eskimos who lived in the north of Greenland began to settle farther south, and there are indications that they intermingled with the Norsemen. Many Norse artifacts have been found in Eskimo sites, and in the fifteenth century the Eskimos began building square houses on the Norse pattern. Early post-Columbian voyagers to Canada mentioned encounters with light-skinned, fair-haired Indians; some assimilation may have occurred.

Finally, a few Norsemen must have clung to the old farmsteads and died in solitude. We have evidence of one such death at a place labeled Farm 167. Here in a fifteen-room house beside a secluded lake a Norse skeleton was found by archaeologists. Most Norsemen were buried in the consecrated ground of the local churchyard. But no one was there to bury this man; he died alone, the last of his kind.

The final chapter in the history of the Norse Greenlanders is full of interesting problems, but we should not allow it to obscure the important fact that the settlements survived for centuries before they were abandoned. In this remote part of the New World, long before Columbus’s voyages, Europeans had established their civilization. After 1492 Europeans would again come to America and would eventually dominate the new continents. But the post-Columbian settlements were not the first Euro-American adventure. In the first the land and the natives eventually prevailed, absorbing the Europeans.

This essay was first published in early editions of American Realities: from the First Settlements to the Civil War