The post that follows began life as a “Fireside Talk” in 2016 in my course on National Parks at Eastern Washington University. Posting in 2020 I want to make it available to a wider audience.

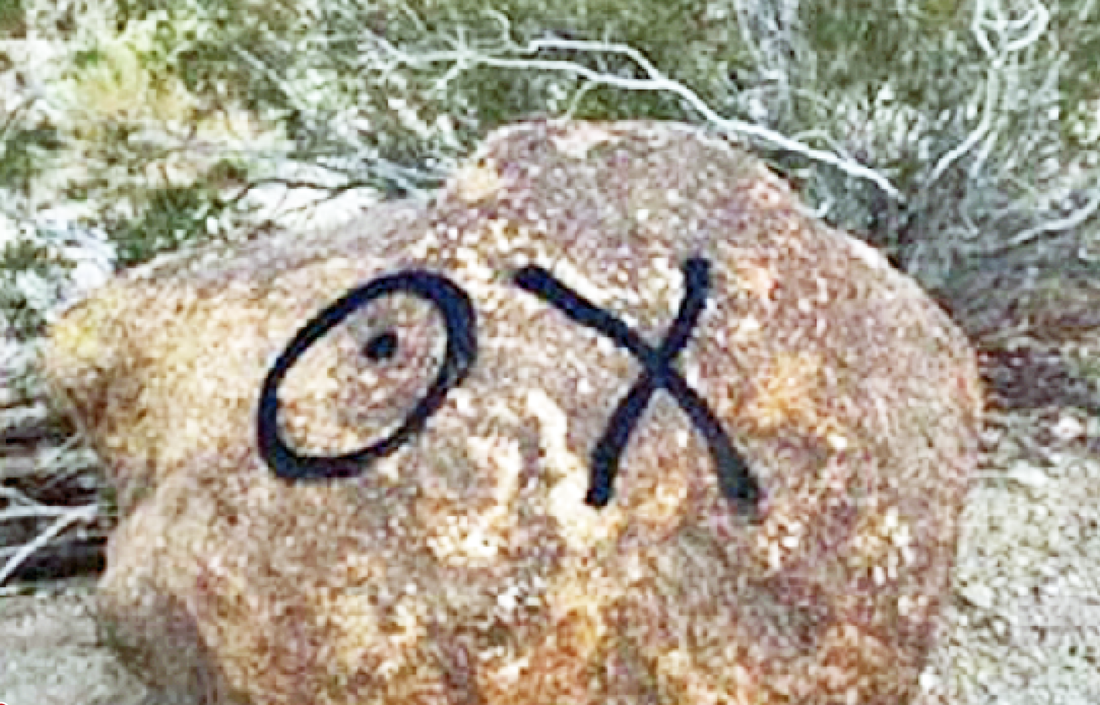

Last week Hannah Bancroft posted the story of an artist named Andre Saraiva and his drawing on a rock in Joshua Tree National Park. Here is the image she included:

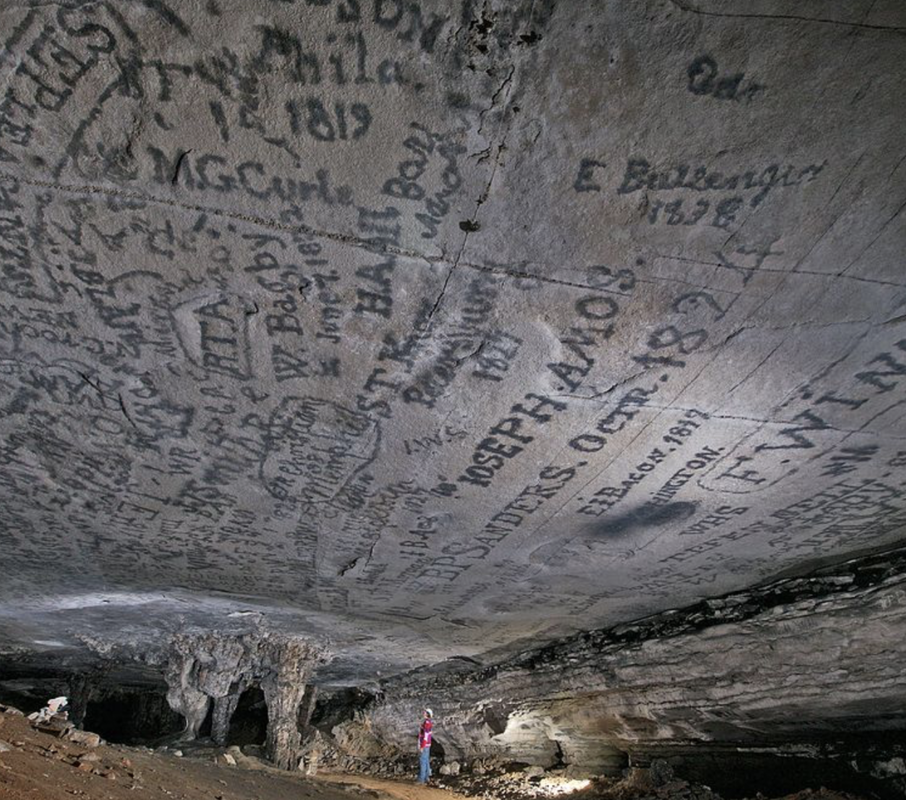

Lauren and Kaitln replied to Hannah's post with more information and more examples of park vandalism. Aaron Ross also replied, but with a different take on park graffiti. Describing Mammoth Cave he wrote: "Historic signatures which adorn the ceiling in the 'Gothic Avenue' portion of the cave are preserved and viewed as part of the cave's tours. The historic graffiti displayed is called 'ceiling smoke writing' which is made using candle smoke to stain the whitish limestone. During the 1800s, visitors were encouraged to write their name on the ceiling of Gothic Avenue" Here is the picture Aaron posted:

(By the way we hear a lot nowadays that writing is not taught as well today as it once was -- but 200 years ago could folks really show such good "penmanship" with a candle on a cave ceiling? I wonder!)

During the early days of Yellowstone, tourists from the local hotels often used sticks to etch their names in the shallow hot springs nearby. Soldiers -- the park rangers of the time -- saw the signatures, found the culprits in the hotel register, and made them remove their names. They regarded these marks as vandalism then, but I wonder if some of those signatures, inscribed more than 100 years ago, might be cherished ikons if they had survived until today.

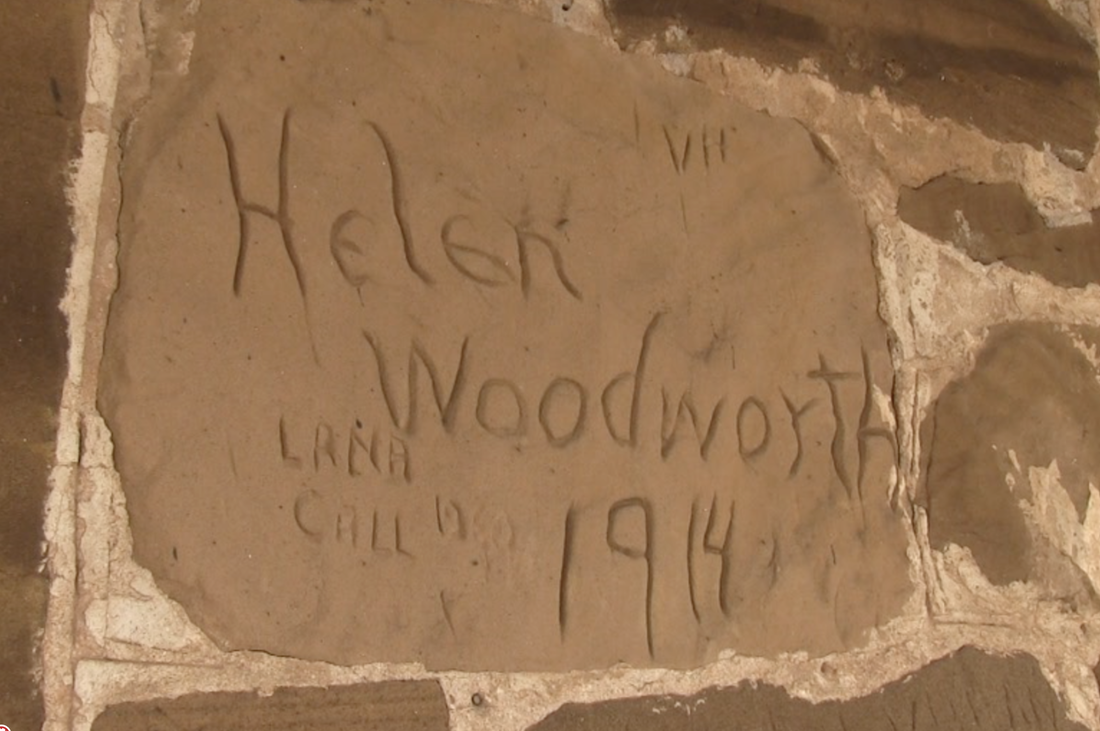

Fort Larned National Historic Site on the Santa Fe Trail provides its own example of graffiti uplifted to history. Here is a picture I took of the long porch on one side of the fort:

So graffiti has been around in the United States for more than two centuries, sometimes deplored, sometimes admired. That is a long time, but yesterday in Jerusalem (2016), I saw evidence of much older graffiti going back nearly 1000 years! I was in a religious site in the Old City, and here is what I saw on one of the walls:

I was with a group of American army officers. (My friend and host Ryan Shaw is a colonel stationed in Jerusalem and was the official guide for this tour, which is how I happened to be along.) Several of the officers -- remembering perhaps the unruliness of some of their own troops, imagined the officers of that far-away time saying to their men: "Stop that! You're dulling your sword blades. We have more battles to fight!"

Be that as it may, the crosses have stood the test of time: they bear witness to a constant human need to leave an enduring mark on their passage through life

So the next time you see graffiti ask yourself, is this a piece of history deserving our respect -- or is it vandalism, plain and simple?

The answer is not always easy to find. But in the mean time, I do not recommend painting any rocks in a national park -- unless you can go back in time for at least a century before posting your artwork!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed