While teaching the history of the American National Parks, I sometimes explore park history and policies in other nations. These journeys abroad with my students at Eastern Washington University (real for me "virtual" for them) give us engaging ways of exploring parks. When I stayed recently at the Hotel New Otani in Tokyo and explored its famous garden, I knew I had some wonderful material for my students back home.

Now admittedly, It is a long way from a Japanese garden in Tokyo to, say, Yellowstone or Yosemite.

Or is it?!

Our class is an exercise in what I like to call "parkology" -- an exploration of key themes and events in the life of American parks. As we study one park, we discover instances of comparable stories in other parks in the United States and around the world. These can be stories about roads and trails, traffic control, animal management, or more broadly, the challenge of defining "nature." So when I posted my students about the Otani Garden, I told them that the lesson was "about a particular park in Tokyo, but also an exercise in exploring other places and events through the filter of our understanding of American parks."

Here are the basic facts about the Otani Garden as presented in the hotel's web site:

With its 400 years of history, the Japanese Garden at Hotel New Otani is one of the most renowned gardens in Tokyo. The vast ten-acre ground, surrounded by the outer moat of the historic Edo Castle, houses numerous kinds of trees, flowers and foliage. Stone gardens and lanterns, carp ponds and waterfalls offer a taste of Japanese tradition and culture to our visitors. People come by to escape from the hustle and bustle of the city, and to enjoy a moment of peace and relaxation in the profound abundance of nature

"Peace and relaxation in the profound abundance of nature...." The chief apostle of the American park movement, John Muir, might have written those very words himself. They sound like this Muir quotation on a magnet that I keep on my refrigerator door:

The parallel is all well and good, but is it accurate to credit a well-groomed garden with natural "abundance"? In this quotation Muir talks about climbing the mountains -- hardly a description of a well-tended garden. But then again, Muir does talk about nature, peace, and relaxation, qualities to be found in this Japanese garden. Here are some views of the 10-acres:

I asked my students some questions via the Internet, while I was posting from Tokyo. They were to review the pictures I've posted above to help them form their opinions. Here are some of the prompts I gave them for considering the garden in the framework of a "parkology" perspective:

• Parkology 1: During the quarter we have noted that there is such a thing as "park-friendly" architecture - "honoring the landscape." But seemingly in painting the garden bridges red, the builders in this case did not follow that principle. Or did they? Is it "all right" sometimes to build structures that contrast sharply with the landscape? Take away the red paint from the bridge, and does it seem more natural? Or, in this case, does the red paint feel appropriate?

• Parkology 2: (a) These are not wildflowers, but they are, obviously, flowers. What American National Parks are especially noteworthy for their flowers? Does a cultivated flower garden retain any elements of a natural setting? (2) Who does not love a waterfall? But does a waterfall lose something in being man-made?

• Parkology 3: The plaque, the statue, and the straw or bamboo tree skirts-were aesthetically pleasing touches, and seemed to me to "honor" this particular landscape. When are such embellishments appropriate? Should we place straw skirts on the redwoods?!

• Parkology 4: You will have to take my word on this... Part of the natural charm of the Otani Gardens is the sounds of nature. The bird sounds were more abundant than on many of my visits to a National Wildlife Refuge near my home, and the sounds of little rivulets and larger falls were omnipresent. Moreover, the human beings there were silent and respectful as in a church.

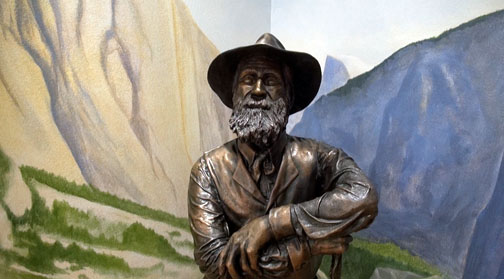

• Parkology 5: I asked the students to consider the statue of Yonetaro Otani (pictured below) who built the New Hotel Otani, but set aside ten acres of enormously valuable Tokyo real estate to preserve the historic garden. Wasn't he similar to Stephen Mather the wealthy philanthropist who became the first superintendent of the American National Park Syste?. The statue sits in one corner of the garden:

Now, I had persuaded myself that much of what we Americans love about wild places can be discovered in a beautiful garden -- the feeling of being in the garden can nurture feelings consistent with those we sometimes feel in the National Parks, but...

I asked my students to post comments on these parkology questions, and they responded with enthusiasm, but not always with approval of my argument that there was indeed full-fledged nature in this garden. The best way that I can continue this narrative is to copy below the post I wrote for my students and uploaded from Japan. Here it is:

November 20, 2014

My heart was heavy as I walked from the Hotel New Otani lobby down a passage to the hotel's Japanese Garden. I would be communicating to the objects there the honest but dispiriting fact that many of my American students did not feel that the garden was, well -- real. Not real nature anyway. Two students, for example, had quoted from Alolph Murie, "Let us be guardians rather than gardeners." One continued, "I thought the garden was very nice, beautiful, peaceful, and relaxing. That being said, it is nature without being natural." And another wrote: "When one visits a national park, there is not a feeling of, wow, it's amazing that we humans are such amazing landscape artists, or painters, or architects. No, it is something else that we experience."

Now honestly, I feel the reasonableness of such reservations. And yet I felt reluctant to pass this news on to the flowers. Would they wilt at the news that they were not truly natural?!

The Creatures Respond

As I looked and listened to the water, it seemed to urge me to remember these words from our friend John Muir: "As long as I live, I'll hear waterfalls and birds and winds sing. I'll interpret the rocks, learn the language of flood, storm, and the avalanche."

"Can you not listen and learn here as well," the water seemed to say. "Is my spray a false spray, and is my sound imaginary?"

Before I could answer, I heard the birds, the many birds in the trees, calling out, "What about us? Are you going to ask us what we think about this nature business?"

They were all chattering together in Japanese, and so I had trouble understanding every word, but then one of them -- apparently the wisest, spoke words that I already knew, written by a native son of my own Washington State, Justice William O. Douglas. Improbable as it may seem, the bird quoted:

Inanimate objects are sometimes parties in litigation. A ship has a legal personality, a fiction found useful for maritime purposes. The corporation sole—a creature of ecclesiastical law—is an acceptable adversary and large fortunes ride on its cases.... So it should be as respects valleys, alpine meadows, rivers, lakes, estuaries, beaches, ridges, groves of trees, swampland, or even air that feels the destructive pressures of modern technology and modern life. The river, for example, is the living symbol of all the life it sustains or nourishes—fish, aquatic insects, water ouzels, otter, fisher, deer, elk, bear, and all other animals, including man, who are dependent on it or who enjoy it for its sight, its sound, or its life. The river as plaintiff speaks for the ecological unit of life that is part of it.

As this loquacious Wise Bird spoke, the whole forest grew silent, the carp stopped swimming, and the very water of the waterfall ceased falling. At the end of the speech, after a brief silence, all the creatures applauded with wild enthusiasm, as best they could. The birds flapped their wings, the carp flapped their tails, the trees flapped their branches, and the water flopped madly over the rocks. As for me, I jumped up and down on one of the red bridges in a noisy gesture of approval.

When everyone, including me, had settled down, the Wise Bird came close to me and gestured for me to follow into a corner of the garden. In case I had missed the point, he explained to me (in broken English) that if I had taken the time to ask the birds and trees and fish and water if they were free agents they would have responded emphatically,"f course, we are!"

Then, speaking for himself, he said, "Many of us are birds, for heaven's sake. We don't have to stay here if we don't want to!"

Click here to view a complete list of entries on the American Realities blog...

(You know you want to!)

If you enjoyed this article you may enjoy these other articles about Parks and Mother Nature:

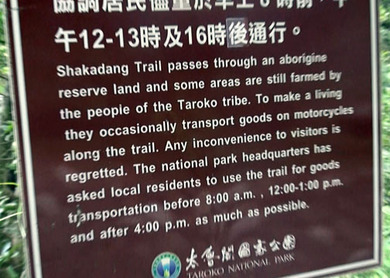

• What's that Motor Scooter Doing on a National Park Trail?!

• New York's Central Park: A Wilderness?

• A Visit to John Muir National Historic Site

• Danger in the National Parks

• Henry David Thoreau and the Felling of a "Noble Pine"

• On the Road with History 498: "The History of the American National Parks"

RSS Feed

RSS Feed