The Kensington Runestone, as it is known, telling the story of Norse exploration in North America during the fourteenth century, was "discovered" on a farmer's land in Minnesota in 1898. Here are some closer views of the Vikings and the Runestone as they appear on the U-Haul Truck:

But what the Kensington Runestone lacks in authenticity it possesses in the power to generate interest in Norse history. The Runestone Museum in Alexandria, Minnesota features the actual 200-pound stone along with a replica of a viking ship and other exhibits relating to local history. While not claiming conclusive evidence for the authenticity of the stone, the museum web page makes the sustainable claim that it has stimulated debate: "For more than 100 years, scientists, geologists, and linguists have studied the stone in an effort to offer a conclusive answer to the question of the Kensington Runestone’s authenticity. Our research library is packed with books and articles exploring the story of the stone."

U-Haul deserves credit for featuring the runestone and other historical themes so prominently on its trucks. The Viking image was rolled out on more than 2,000 trucks in 2011. The Kensington Runestone pictures, along with the thousands of other historical images on U-Haul trucks are undoubtedly the most numerous rolling history lessons in the United States. In the case of the runestone, this story will prompt some viewers to look deeper into the history of the early Norse explorers and settlers in the New World.

While the famous runestone is most likely an artifact of the imagination carved by a clever practical joker, other episodes in Norse history are authenticated by stone, skeletons, and documents. As for norse settlers, they came to the New World in the thousands, and stayed for more almost five centuries. In making this statement, I am including Greenland, where the Norse established towns on the southwestern coast. From there they planted a settlement in Newfoundland and they often visited the coast of Labrador to trade with the native peoples and to gather timbers for their settlements.

A few years ago, I wrote an essay on the Norsemen in Greenland for the first edition of American Realities, the book after which this web site is named. In the article I summarized current information about those ancient pioneers and attempted to "reconstruct" various elements of their lives based of research into current literature on the settlements.

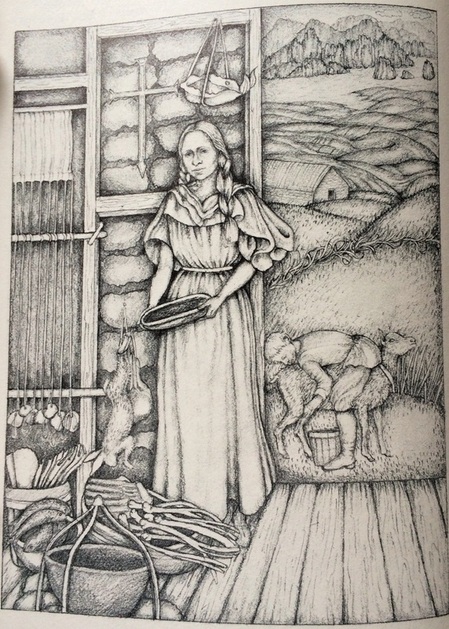

Artist Cecily Moon created this image to accompany the essay.

First we have the houses. Faced with winter temperatures of 40 degrees below zero, even on the seacoast, and with strong winds common, the settlers had to build dwellings that would be warm and solid. The early houses were chiefly great halls or main rooms, which served for living, eating, and sleeping. They were made with thick earthen walls and roofs of timbers, sod, and rocks. A central firepit provided warmth, light, and cooking.

These early halls resembled the dwellings of Iceland and Norway, but over the years a new pattern was formed. The large halls, probably too cold and drafty, came to be divided into smaller rooms. At first the great hall was split into two or three rooms. Late in the thirteenth century the “centralized farm” became common. These were large complexes encompassing from fifteen hundred to six thousand square feet and sometimes included rooms for animals. The precious cattle were placed at the very center of the structures.

Heat was provided by thick walls and furs and by modest fires. Probably the settlers spent most of the coldest days wrapped in robes, huddled together, fingers too chilled to spin wool or carve soapstone implements. The driftwood that was almost their only fuel can hardly have been plentiful enough to allow large fires every day. In especially cold times they must have been driven to cut scrub brush growing nearby, though it was needed to keep the winds from ripping away the pastureland. At times, winter isolation might be broken by a visit of neighbors, and in celebration a large fire and huge meal would be prepared. It was around such fires that tales were told that matured into the great Norse sagas. Then the guests would leave, and the family would be left alone in the wind and cold through the long dark winter.

Clothing, too, was influenced by the Greenland environment. Norse graveyards show us that the people sometimes dressed in the hooded, ankle-length woolen gowns worn in Norway. We know the settlements lasted well into the 1400s, because skeletons have been found clad in hooded capes and caps that were worn in Paris and Burgundy late in the fifteenth century. But one wonders if the Norse farmer wore a costume like that to tend the cows or his wife spun and cooked in her woolen gown. The day—to—day costume was more often made from the skins of deer, seals, or cattle. Sealskin trousers and heavy double fur coats were popular.

During many centuries trade was common between Europe and the far-flung settlements in Greenland. The Catholic Church posted priests and bishops on the remote island, and church tax revenues from Greenland helped build St. Peter's in Rome. Some of the bravest men and women in the world were those who experienced the icy waters of the North Atlantic in the open boats known as Knarrs. Among the "treasures" of the New World carried back to the Old were polar bears for European display. (The crest of modern-day Danish monarchy still includes the image of a polar bear.)

I've posted the Norse essay on this site at this location: "The First Euro-Americans: Norsemen in the New World."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed