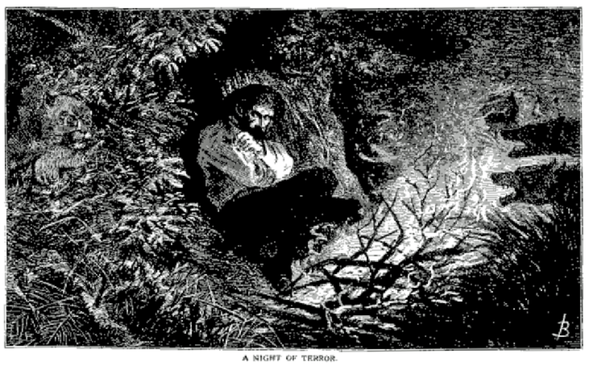

Truman Everts in his account of being lost for 37 days during an 1870 exploratory expedition into Yellowstone.

Drawing is from his article in Scribner's Monthly, 1871.

Such tragedies are common in the National Parks, and naturally, park officials take every step possible to avoid them. The men in this episodes undoubtedly were seeking nothing more exciting that a peaceful walk up a lovely canyon--not inviting danger or death. But many park deaths come from inherently dangerous activities. A few months ago two BASE jumpers were killed in separate accidents in Zion National Park. BASE jumping--also known as proximity flying--is one of the most deadly as well as one of the most thrilling outdoor sports. For many adventurers the exhilaration outweighs the risk. A friend of one of the deceased jumpers has now lost five friends to BASE-jumping deaths during the past year, but says that he intends to continue jumping: "It's a personal choice," he told a reporter.

Still image from YouTube video: "Proximity Jumping with Jokke Sommer"

(Be sure to click on this link for an amazing ride!)

Truman Everts was an early embodiment of the association of parks and danger. He became a kind of hero for his ordeal and was even offered the position of superintendent of the world's first national park. The position provided no salary and so, understandably Everts refused the offer: he had already starved once in Yellowstone.

Another chapter in the story of danger in Yellowstone came in 1877, the year after the region became a National Park. Men and women camping there that summer anticipated no more excitement than bears, buffalo, geysers, and canyons could provide, but found themselves in the middle of an Indian War. Fleeing government troops in the Nez Perce War, Indians came through the park, captured several tourists, killed two and wounded others.

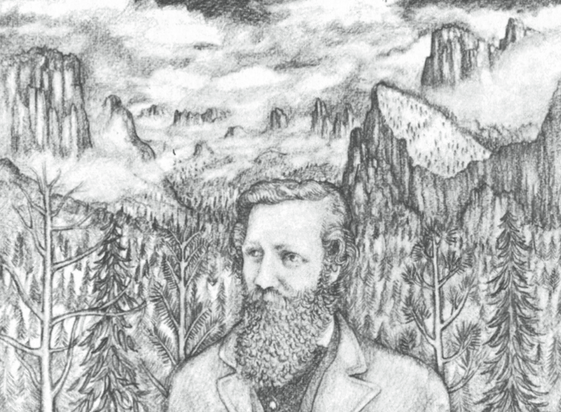

These episodes made great press for outsiders, but they were not invited by the participants. Deliberate risk-taking , however, also goes back to the early days of the parks. None was more daring in experiencing nature than the High Priest of the National Parks movement, John Muir.

from "The Birth of Environmentalism: John Muir and the American Wilderness"

One fine summer day in 1868 the young John Muir stood by a cliff edge hung over the Yosemite Valley. A half mile below, the land “seemed to be dressed like a garden—sunny meadows here and there, and groves of Pine and Oak.” Nearby the Yosemite River cascaded through a channel in the rock, sped down a short incline, and sprang “out free in the air.” Muir wanted a clear sight of the waterfall and began to work his way down the rock. Below he could see a narrow shelf that might support his heels over the sheer cliff. He filled his mouth with artemisia leaves, hoping the bitter taste would prevent giddiness. He then worked his way along the ledge; it held him, and he was able to shuffle twenty or thirty feet to the side of the falls. There he found what he wanted—“a perfectly free view down into the heart of the snowy, chanting throng of comet-like streamers, into which the body of the fall soon separates.” In camp after dark that night he recorded in his journal that “the tremendous grandeur of the fall” had smothered all fear. He had had a “glorious time.”

So, would John Muir ever have gone BASE jumping? You could say no, because he liked to know the wilderness with his legs planted on the ground--and sometimes with his hands on the trunk of a tree or the side of a cliff. And yet, arguably he did engage in a kind of spiritual proximity flying:

He often reflected on death and had faced it many times in the mountains. He spoke of it as “going home.” After death the soul would be free to wander through the wilderness uninhibited by a physical body and earthly cares. He once described how he would begin that pilgrimage: “My first journeys would be into the inner substance of flowers, and among the folds and mazes of Yosemite’s falls. How grand to move about in the very tissue of falling columns, and in the very birthplace of their heavenly harmonies, looking outward as from windows of ever-varying transparency and staining!”

That sounds like a slow-motion version of proximity flying, doesn't it?!

(You know you want to!)

If you enjoyed this article you may enjoy these other articles about Americans and Mother Nature:

• A Visit to John Muir National Historic Site

• A Winter Walk alongside the Grand Tetons

• "Oh Beautiful for Spacious Skies"-- Reflecting on a National Anthem...

• Henry David Thoreau and the Felling of a "Noble Pine"

• Swimmers at Walden Pond: Henry David Thoreau and his Successors•

• On the Road with History 498: "The History of the American National Parks"

• Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, Resplendent in Greens and Yellows

• New York's Central Park: A Wilderness?

• In Praise of Clouds: America's Unsung Beauty

RSS Feed

RSS Feed