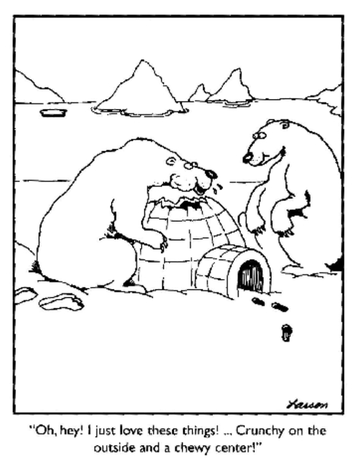

Now, I know that some of you will think of me as a "wilderness wuss" what with my finding wildness in a Japanese Garden or a city street. So, in my defense, have a look at my about the death of a polar bear. I'm deep in the arctic, for heaven's sake. More polar bears than people up there! (See Polar Bear post.)

So I know and cherish many places that are way, way "out there" on Roderick Nash's scale of wilderness saturation levels in Wilderness and the American Mind. But that said, I claim two points for my argument that I was in the wilderness when I saw this evening sky from a Spokane street.

Before I make my case, here is the scene I am writing about:

1) As Roderick Nash contends there is a spectrum of wildernesses ranging from way out there to not out there at all, and as I have argued in an earlier post, clouds are a form of wildness -- often beautiful, sometimes threatening, never by-us controlled. Moreover, the entire universe whether out in other planets and galaxies or right hear on earth is pretty wild. Our cities are kinds of "pods" in the midst of nature. Mark Watney in "The Martian" had his "hab" and his rover and his suit as his pods on an otherwise uninhabitable planet. Our pods, whether individual houses or giant cities, are far more elaborate and are surrounded by air we can actually breathe and temperatures we can actually endure. But we still life our lives in the midst of natural processes that we only partially control. Those impressive clouds over Spokane are a reminder of the natural world.

2) Measuring wilderness is also a matter of measuring our receptiveness to the natural world. I have been in a crowd looking at a waterfall in the Grand Tetons and experienced a lot more of the noisy crowd there than felt the presence of the actual falls. And I have seen a hawk flying over my house that made me, in that moment, stand in awe of the natural world. It's subjective. What are our receptors are receiving. And on that evening when I took this picture, I was much more sensing the wonder of the natural world than focusing on those concrete and glass walls.

My conclusion: wildness, Mother Nature, wilderness -- call it what you will -- we live in the midst of it and our awe-struck awareness of this fact comes upon us in National Parks and Arctic landscapes, but it is not a "tame lion" and sometimes it visits us in unexpected ways.

So be awake and aware -- and enjoy the journey!

Click here to view a complete list of entries on the American Realities blog...

(You know you want to!)

If you enjoyed this article you may enjoy these other articles about Parks and Mother Nature:

• New York's Central Park: A Wilderness?

• The Japanese Garden at the Hotel New Otani -- an Exercise in "Parkology"

RSS Feed

RSS Feed