Visiting an Extraordinary College Graduation with Words, Images, and Music

Writing this evening I've chosen one of my favorite such moments, a graduation ceremony of June 10, 1875, at Hampton Institute, one of the first colleges founded after the Civil War to educate African-Americans. Lacking an actual time machine, I will attempt herewith to "visit" and recreate that episode through words, images, and song.

Booker T. Washington and the Hampton Experience

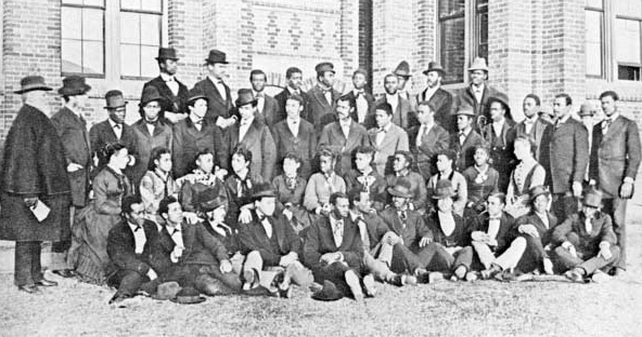

Source: Booker T. Washington National Monument

For Booker T. Washington, the journey began in slavery. As a child he lived with his mother in a little log cabin with a dirt floor. "The wind blew freely through cracks in the walls and doorway," Washington recalled, "making it bitterly cold in the winter. At night the children lay on the dirt floor." In his Autobiography, Up From Slavery, Washington described the excitement on the plantation during the days before emancipation. (Quotations here and below are from my essay, "Beyond Emancipation: Booker T. Washington and the Atlanta Compromise" in American Realities. The quotations within these excerpts are from Washington's Up From Slavery. )

Out of deference to their southern masters, and perhaps from fear of punishment, they did not openly express their northern sympathies. But their excitement grew with each year of the war. Washington remembered awakening one night in his bed of rags and seeing his mother kneeling over her three children praying for the success of Lincoln’s armies. The yearning for freedom pulsed through the slave quarters. Night after night blacks stayed up late to sing their plantation songs, which contained words about freedom. The slaves had once associated these words—for their master’s benefit—with the next world, but now the songs took on a new, bolder tone; the slaves “were not afraid to let it be known that the ‘freedoms’ in these songs meant freedom of the body in this world.”

When he was sixteen, Booker T. Washington heard about a newly-established college for African Americans named the Hampton Institute, and he decided he would attend. Despite the opposition of his mother, who thought he was embarking on "a wild goose chase," he saved a little money, and with the help of neighbors who chipped in variously with a quarter or a nickel or a handkerchief, he boarded a stage coach and headed for Hampton. When the stage stopped for the night, and the white passengers found room at an inn, Washington had to sleep outside in the cold -- no room for blacks. When he reached Richmond, Virginia, about 80 miles from Hampton, he was so poor than he slept outside under a board sidewalk. He worked for a few days unloading ships and saved enough money to continue his journey to Hampton:

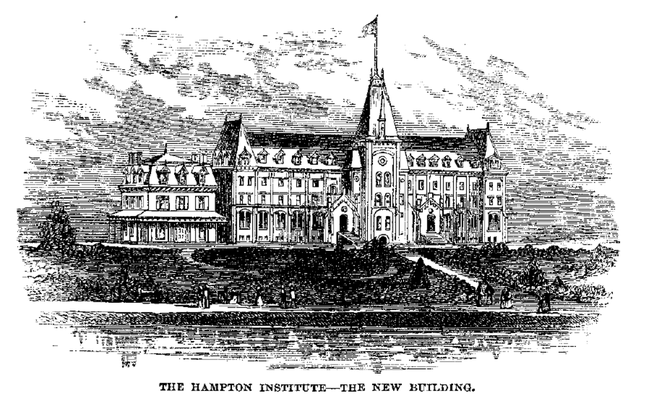

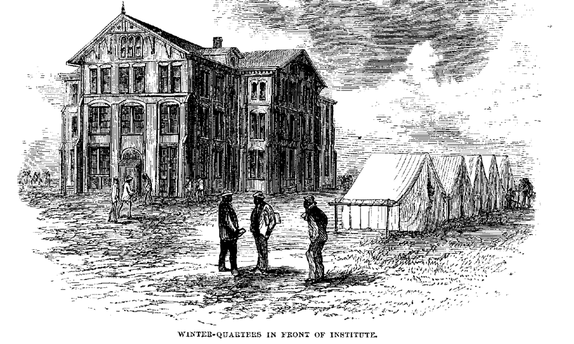

As the school appeared before him, he was struck with wonder. The academic building was an imposing three-story edifice. Undoubtedly he had seen larger buildings in Richmond, but none dedicated to the education of his people. “It seemed to me,” he later recalled, “to be the largest and most beautiful building I had ever seen.”

His three years at the Hampton Institute were spent in rigorous physical and intellectual labor. The students arose at 5:00 a.m. and were inspected for dress and grooming forty-five minutes later. At 6:00 a.m. they had breakfast, then prayers and room inspection. Classes and study hall occupied most of the remainder of the day. The curriculum included reading, geography, history, algebra, government, natural science, and moral philosophy. Hampton was a trade school as well as an academy, and the students worked as waiters, farmers, janitors, carpenters, painters, printers, and shoemakers.

There was much to like about Hampton and many men and women to admire on the faculty. Above all, there was the head of the school, Gen. Samuel Chapman Armstrong, of whom Washington said, “I never saw a man who so completely lost sight of himself.” Armstrong was a slender, soldierly man who had risen to command as a youth in his twenties during the Civil War. A northern idealist, he had resigned from the army after the war in order to devote his life to the education of the former slaves. As the school’s head he seemed to embody its emphasis on hard work, liberal intelligence, and moral rectitude. The students were so devoted to him that one winter when the men’s dormitory became overcrowded, almost everyone in one class volunteered to sleep outside in tents. Each morning during that cold season the general came by the tents to see how the men were doing, and out of loyalty to him they never admitted their acute discomfort in the canvas dwellings. Armstrong became like a father to Washington, helping the young man with his career and providing a role model for his work as an educator.

Source: Wikipedia Commons

Commencement Ceremonies at Hampton Institute, 1875 -- First Glance

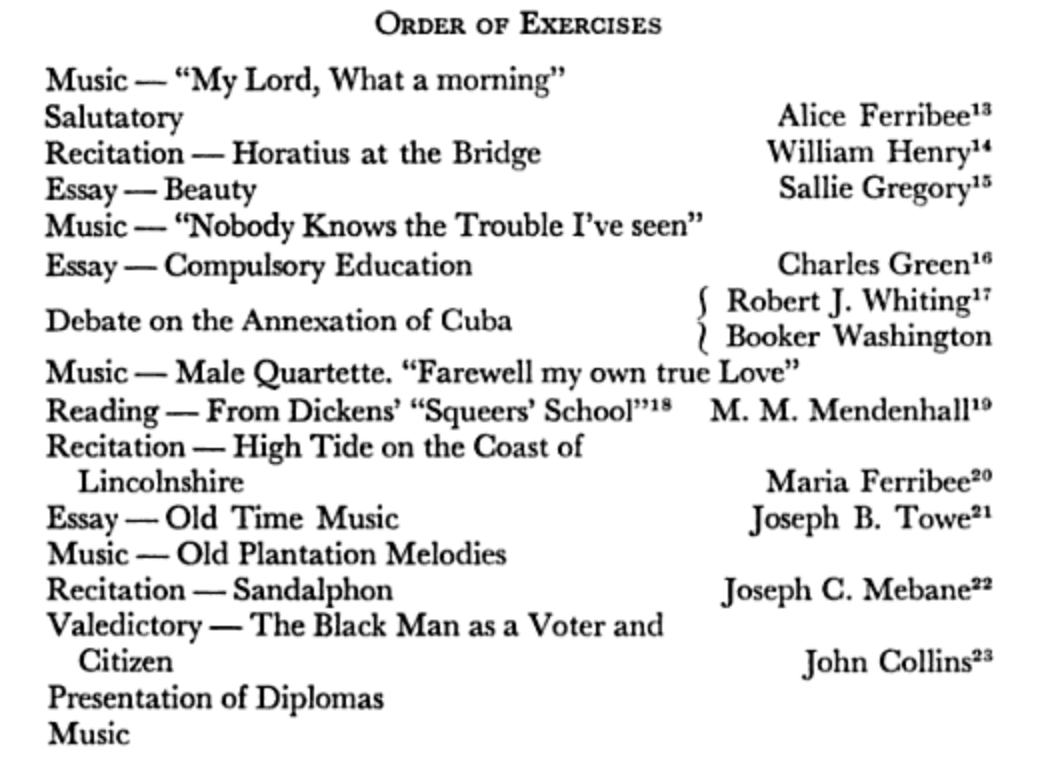

The promise and achievement of the Hampton Institute was symbolized by the commencement exercises in June 1875, an impressive event attended by both black and white observers, including journalists from northern newspapers and magazines. Several students recited poetry, and a chorus sang “Farewell My Own True Love” and “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.” Seniors read their essays on “Beauty,” “Compulsory Education,” and “The Black Man as a Voter and Citizen.” Washington and another student debated “The Annexation of Cuba,” Washington taking the negative side and impressing several reporters with his forceful oratory and keen logic.

The most engaging performance of all was a lecture on slave music by a student, Joseph B. Towe. A reporter from the Springfield Daily Republican was spellbound by the presentation. “The writer,” he said, “himself brimful of song, a powerful soloist, with a voice of wonderful sweetness, took us back into the past of slavery, and even further back, into Africa itself, for the original sources of this strange music.” Towe described the work songs of his own plantation days “when the fields were full of music.” Slave soloists were especially important, leading the field hands in song. They drew a large price from plantation owners, “for it paid well in the increased amount of work when the air was alive with work songs.” Towe remembered one soloist, John Jones, who could speak an African language.

He recalled the cadences and variations of the work songs. “I will give you an instance,” he said, and a chorus of students began to sing. The music, born in Africa, nourished through generations of slavery, uttered now by a chorus of young emancipated black students, swelled through the auditorium. Towe continued his lecture, pausing again and again while the students illustrated his points with song. The audience was entranced, and even former secessionists congratulated the school for its fine program.

Booker T. Washington’s career at Hampton ended in a celebration of his people’s past achievements, current attainments, and future hopes....

I wrote those lines long ago, on a typewriter, before there were personal computers and an internet. Much has changed since those days, but technology has not yet brought us a serviceable time machine. And so I am left with "wishing I were there." And yet, and yet....

Modern technology does encourage journeys of the imagination that would have been more difficult several decades ago. For one, we have better access to historical books are documents and even music than in the past. And so, from my office I've been able to delve deeper into the story of the Hampton Commencement of 1875 and it's background.

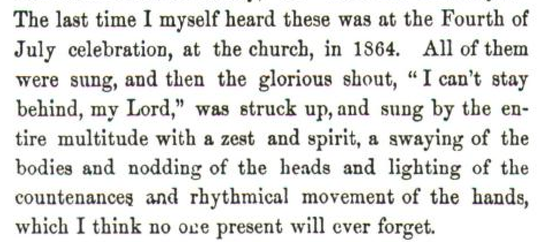

The extraordinary outburst of song at Hampton on that June day drew upon a tradition of exhibiting slave music performed by freedmen that began more than a decade before at Port Royal, South Carolina, In 1861 Union forces occupied the area and began a process historian Willie Lee Rose called Rehearsal for Reconstruction. The agents of a northern mission sent south to bring education to the freed slaves were impressed by the "rich vein of music" they discovered at Port Royal. In Slave Songs of the United States (1867) -- the first book on the subject -- the authors reported, "When visitors from the North were on the islands, there was nothing that seemed better worth their while than to see a 'shout' or hear the 'people' sing their 'sperichils.'" One of the authors wrote of the slave songs:

A Closer Look at Hampton in the 1870s

None the less, the slave music was popular throughout the country when Booker T. Washington arrived at Hampton Institute. At Fisk University, a new black institution opened in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1866 an teacher names George L. White was assigned to instruct the students in music and encouraged to let them sing "their own music." They performed concerts featuring slave music in Nashville and its environs. Well received, White took a group of singers on tour in 1871, and they became known as the "Fisk Jubilee Singers." Soon other schools, including Hampton Institute, toured music groups of their own.

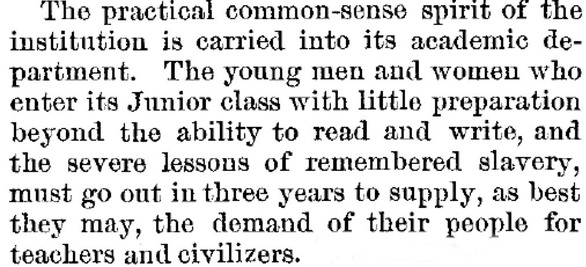

In attempting to "visit" Hampton at that time, probably our best guide is Helen Wilhemina Ludlow, who wrote a lengthy article for Harper's Magazine in 1873 describing the campus. At that time many of the students had actually begun life as slaves. She writes:

Helen Ludlow was struck again and again, however, by the energy and idealism of the Hampton students. "How many white boys," she wrote, "could be found in this generation, I wonder, who would, in spite of lameness, walk sixteen miles daily in all weathers, and over a rough Virginia road, for their schooling? How many sisters could bear them company?... There are Hampton students who make these sacrifices, and greater ones, for the privilege of an education."

On the subject of those "greater sacrifices" Helen Hudson furnished more details than appear in Booker T. Washington's account of the students who slept in tents for the sake of the school and their beloved leader, Samuel Chapman Armstrong.

Here "wild strains" of music "came floating over the water."

Source: Hampton University Archives

Visitors were impressed by the Hampton students. "The girls were dressed plainly and neatly," one wrote, with no attempt at display, and they, in common with the young men, conducted themselves with unassuming dignity." At classroom exercises where the students spoke on such topics as "Analysis of the Nature of Man" the Hampton students, only a few years from slavery, "did as well as could any college class of white students on such abstruse topics."

One of the reporters carefully reproduced the commencement program::

Several reporters selected Booker T. Washington for special mention. He had taken the negative in a commencement debate on the annexation of Cuba. One writer noted that Washington made "a very terse, logical and lawyer-like argument." Others reported approvingly on student poetry recitations and original compositions on such topics as "Compulsory Education." But they saved their fullest praise for the student music at the commencement: "The music interspersed throughout the exercises had been the best of its kind and fairly electrified us again and again."

The most "electrifying" performance of all, was a talk by Joseph B. Towe, once a field hand, and now a graduating student. He delivered a talk on "Old Time Music," describing the music of slavery. He noted three kinds of music, "the spiritual, the work songs, and the comic." He argued that all slave music was "derived from native African airs." The planters often paid "a large price" for a good soloist, "for it paid well in the increased amount of work when the air was alive with the work songs."

It was a historical and illustrated analysis of the plantation music. The writer, himself brimful of song, a powerful soloist, with a voice of wonderful sweetness, took us back into the past of slavery, and even further back, into Africa itself, for the original sources of this strange music. It flowed straight from the invisible fountains of the heart, its joy or sorrow leaping forth into music.

One reporter wrote that he listened "to the songs of these young men and maidens, all born in slavery, wherein there were tones which thrilled the very heartstrings, and... seemed to be vibrating with the incredible pain and longing of the years of bondage." The "sweet and moving" words of the songs "drew tears from every eye."

Seasoned reporters, familiar with many college graduations, claimed that this was the best they would likely ever see. "I do not hesitate to say there will be nothing better, nothing half so effective, at any of the coming commencements." Towe's talk was said to be remarkable for "originality of conception, beauty of expression, earnestness, and power to sway the feelings." Another writer claimed, "there has been nothing to equal it at Yale or Harvard in a dozen years." The effect of Towe's lecture with its music was "simply indescribable." Several speakers after Towe commented that other schools might spend one thousand dollars for commencement music that could not match what they had heard for free at Hampton.

Former Yankees and former Confederates at the commencement exercises united in congratulating Hampton and its graduates. But probably none were unaware of the challenges that lay ahead for the young men and women who were leaving Hampton to teach school. One young man at the commencement had, like Booker T. Washington, taught school before coming to Hampton, taught and almost died in the effort. He had to flee to the woods one day, barely escaping a lynching party that murdered two of his assistants. He could not even talk about the episode during his first year at Hampton.

But the atmosphere at Hampton that June afternoon was predominately upbeat. As one reporter noted: "It was a cheering thought after these Commencement exercises that this band of modest, sensible, and intelligent men and women were going abroad through the South to be teachers and leaders of their race."

Hearing the Music

These newspaper accounts and illustrations have brought me closer to fulfilling my "Wishing I were There" thoughts about Hampton's triumphant graduation ceremonies of 1875. But can I go even closer, and bring my readers with me? With this goal in mind, I've been seeking accessible music sources that might at least approximate the music of that moment. Here are a few offerings along that line....

One of the songs on the commencement program was "Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen." We can't recapture the actual music of 1875, but we can travel back about 80 years and hear Paul Robeson sing the same song that filled the church at Hampton that graduation day.

Paul Robeson sings "Nobody Knows the Trouble I've Seen":

Afterword: Another Echo -- the Quaw's Quest Ceremony in Barbados, 2013

One of the delights in being an historian is in seeing the pieces of the puzzle of our past come together in ways both marvelous and unexpected. Earlier this year I attended an international conference on "Africans in the Americas: Making Lives in a New World, 1675–1825" sponsored by the Omohondro Institute of Early American History of Culture. The location was the Cave Hill Campus of the University of the West Indies.

I decided to go in part to hear the many speakers from throughout the Atlantic World. Additionally, I looked forward to studying slavery for a few days on an island were 90 percent of the residents were the descendants of African slaves. The conference was scheduled carefully in advance and was excellent; the lessons from Barbados itself were serendipitous and exceptional.

It turned out that during the time of our scholarly meeting, the University of Barbados was unveiling a monument consisting of the names of the 140 slaves who had lived at the time of their emancipation on the lands that would become the Cape Hill campus. Like the graduation ceremony at Hampton, the Camp Hill celebration included a wonderful range of speakers and musical events. My favorite was a group of school children who had been coached by Anthony "Gabby" Carter, the nation's most esteemed folk song artist, to sing a song he wrote for the occasion: "Crying for Me Ancestors." Alas, I did not have my video camera with me at that moment, but I did have my trusty iPhone and made this little film of Barbadian grade schoolers singing about their ancestors.

This song resonates with my memories of Hampton in 1875. I hope it is has that appeal for you as well....

Click here and see more entries on the American Realities blog.

(You know you want to!)

This current post is one of a growing number of historically-themed entries on americanrealities.com.

For more information about Booker T. Washington on the American Realities web site click here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed