The 2016 Republican Platform and an the Reemergence of Park Pushback

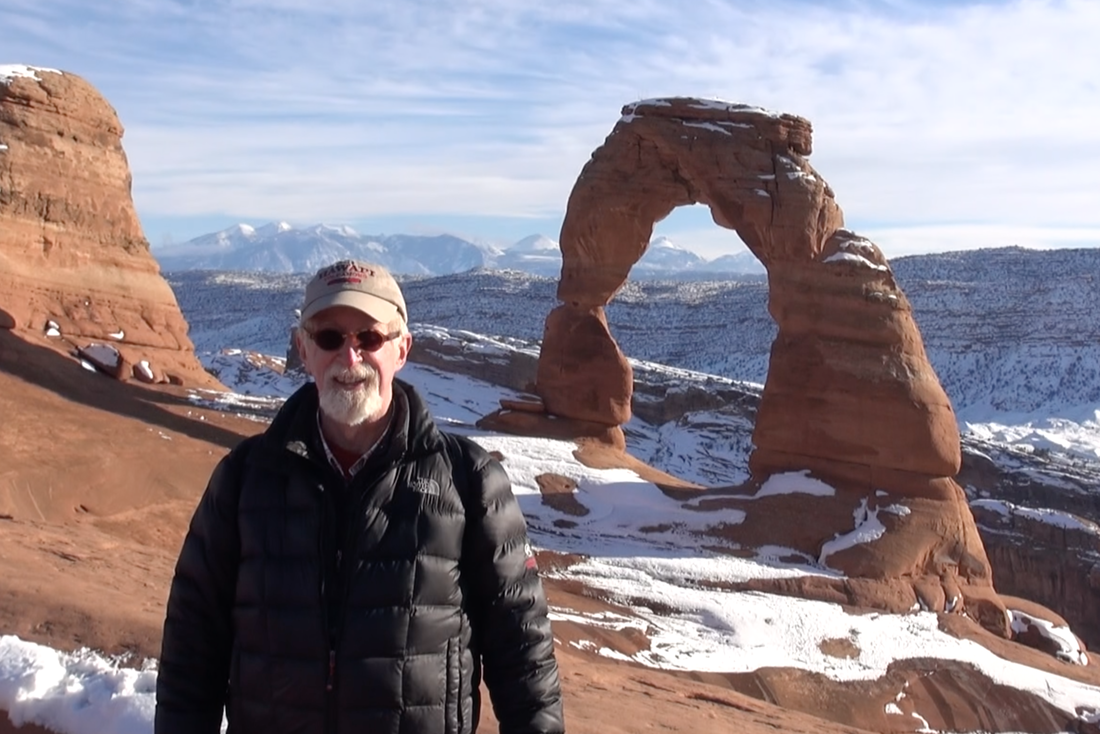

(Arches began its' park life as a National Monument in 1929.)

Why should we care?

History provides the answer. But first, a brief primer on parks and monuments:

National Monuments are units of the National Parks Service. You sometimes hear that there are fifty-nine national parks in the United States. At this writing the actual number is more like five hundred.

Confusion arises from the fact that the National Parks Service, created in 1916, is a collection of parks with many different designations. We have national monuments, battlefields, cemeteries, historic sites, seashores, lakeshores, rivers, recreation areas, parkways, and trails, among designations.

If a park is called simply a “National Park,” it is one of an elite fifty-nine, often esteemed more than the other parks. Recently, for example, Pinnacles National Monument in California became Pinnacles National Park. In describing the change, newspapers referred to Pinnacles as having been “elevated” to its new status.

But this pecking order does not always make sense. Is Hot Springs National Park in Arkansas really more grand than Devil’s Tower National Monument in Wyoming? Is Shenendoah National Park more inspiring than Cape Cod National Seashore? Sometimes the designations seem quite arbitrary.

National Monuments range greatly in size and content. Some are famous landscapes: Devil’s Tower, Mount St. Helens, Canyon de Chelly, and Muir Woods, for example. Others are historic places such as buildings associated with George Washington, Booker T. Washington, and George Washington Carver. One National Monument is literally a monument, the Statue of Liberty.

Grand Canyon (1908, 1919)

Arches (1929, 1971)

Death Valley (1933, 1994)

Pinnacles (1908, 2013)

Dry Tortugas (1933, 1994)

Grand Tetons (1929, 1943, 1950)

The Tetons are a special case: the mountains themselves became a National Park in 1929. John D. Rockefeller Jr. and others wanted to include the beautiful valley known as Jackson Hole in the park, but they faced stiff local resistance. So by executive order President Franklin Roosevelt set aside the valley as a National Monument in 1943. Eventually in 1950 the monument was folded into today’s more expansive Grand Tetons National Park.

The ability of presidents to create national parks by executive order is exactly the power being challenged by the current Republican presidential platform. National Parks require congressional approval as well as a president’s signature. In contrast, the president has a free hand in creating National Monuments—except in Wyoming, by the way, but that’s another story. Additionally, the Republican Platform calls for requiring state legislative approval of new monuments.

But again, why should we care? Shouldn’t “the people” control the park designation process?

Let's go back one century. History provides the answer. Let’s take the Grand Canyon,or example–surelyone of the most national-park-worthy sites in the world. Wasn’t it obvious that it should become a National Park?

Well, no.

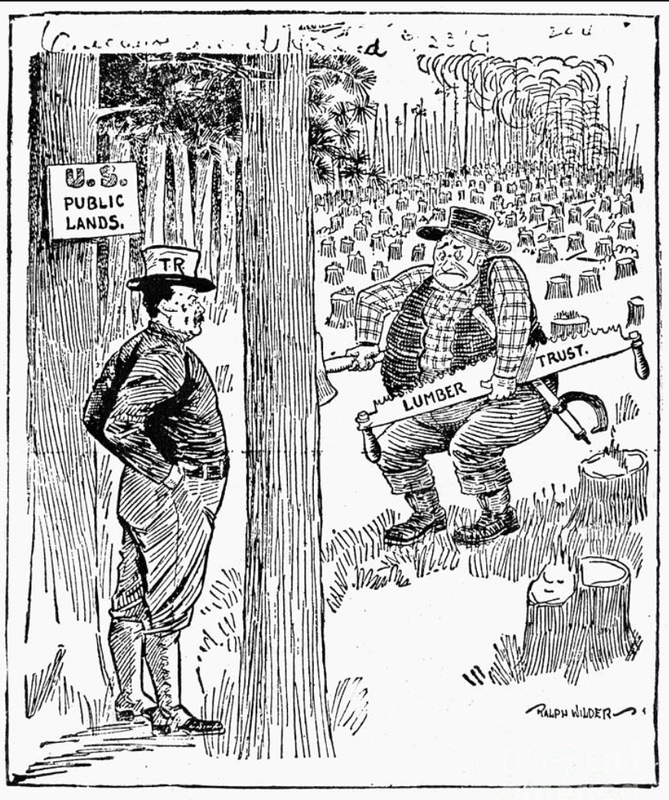

Back in the day, at the beginning of the twentieth century some folks wanted to use the canyon for mining, others wanted private control of tourist access, and some wanted both. The canyon was in danger of being diminished before it could become a park. A new law came to the rescue....

In 1906 during the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, Congress passed the American Antiquities Act, which declares:

“The President of the United States is hereby authorized, in his discretion, to declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Government of the United States to be national monuments.”

Theodore Roosevelt, arguably the greatest conservation president in American history, was eager to protect the canyon. “Let this great wonder of nature remain as it now is,” he declared during a visit to the canyon. “You cannot improve on it. But what you can do is keep it for your children, your children’s children, and all who come after you, as the one great sight which every American should see.” In 1908 he used the Antiquities Act to declare the Grand Canyon a National Monument.

In all Roosevelt established eighteen national monuments including all or part of landscapes that later became Olympic, Lassen Volcanic, Pinnacles, and Petrified Forest National Parks.

Then and now there were persons who opposed such measures, arguing in the name of “the people” that the lands should be open to exploitation. Of course, with the National Parks movement we have adopted a more broad and generous definition of "the people," that includes more than “developers” and more uses than extraction. The people and the parks have come to be synonymous. And over time, again and again, local opponents of a particular park have come to see the economic and scenic value in conservation.

The Antiquities Act granting the president the power to create National Monuments has often protected American landscapes and historic sites for the greater good of us all.

So as we celebrate the centennial of the National Parks Service this year, we should remember also the centennial-plus-a-decade of the Antiquities Act—and the good work of the Republican president and great conservationist, Theodore Roosevelt in putting it to work!

Click here to view a complete list of entries on the American Realities blog...

(You know you want to!)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed