I think of the battle, however, on a more personal level through my affinity for my great-great uncle, William Wheeler, captain of the Thirteenth New York Artillery. He died long before I was born, killed outside of Atlanta in 1864. But I feel his presence in my life more than that of any other unmet ancestor. Partly this is because my mother grew up living next door to William Wheeler’s sister, her grandmother. As a child in grade school, when feeling sorry for herself, she used to weep quietly and tell her teacher, whose attention she craved, that she was crying because her uncle was killed in the Civil War. Those moments were somewhat “stagey,” to be sure, but there must have been moments in her childhood when her grandmother’s memory of her brother was genuine and palpable.

Then too, I am drawn to William Wheeler because of a family artifact, a nineteenth-century hutch that sits nearby as I write these words. William’s brother John Wheeler purchased this ornate piece of furniture after his own service in the Civil War, which included some time in Andersonville prison. An artifact does have a power to evoke the past.

Most of all, I admire William Wheeler because he had a wonderful way with words. He wrote many letters home before and during the Civil War. His mother published them privately in a volume called In Memorium. A few years ago I wrote an essay on two soldiers in the Civil War, one Northern and one Southern, and Wheeler was an easy choice for the union soldier. (Charles Colcock Jones is the Confederate.) The passage that follows is from that essay; it tells the story of Wheeler’s experience at Gettysburg. I’m posting it today along with some pictures I took at Gettysburg during the summer of 2012.

• You can read the entire essay by clicking on the link beneath the text on this page.

• A former student of mine, Guy Breshears, edited the William Wheeler’s Civil War letters from In Memorium for a book titled: Loyal Unto Death: A Diary of the New York 13th Artillery.

Capt. William Wheeler at Gettysburg

Wheeler’s regiment was never required to wait long for that next engagement. For two years they fought indecisive skirmishes and battles in Virginia. Then one day in 1863 the army began to move north, following Robert E. Lee into Pennsylvania. The men, who had lived for months in the South, were pleased by their reception as they marched through Frederick County, Maryland. Children waved handkerchiefs and tiny flags; hotels were wrapped in red, white, and blue bunting; an old lady stood at her door handing out cups of cold water to thirsty soldiers; her gray-haired husband stood at her side, his eyes half filled with tears. “Good luck to you boys,” he murmured, “God bless you.”

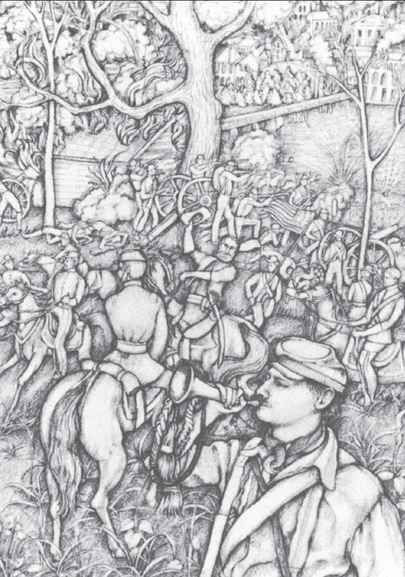

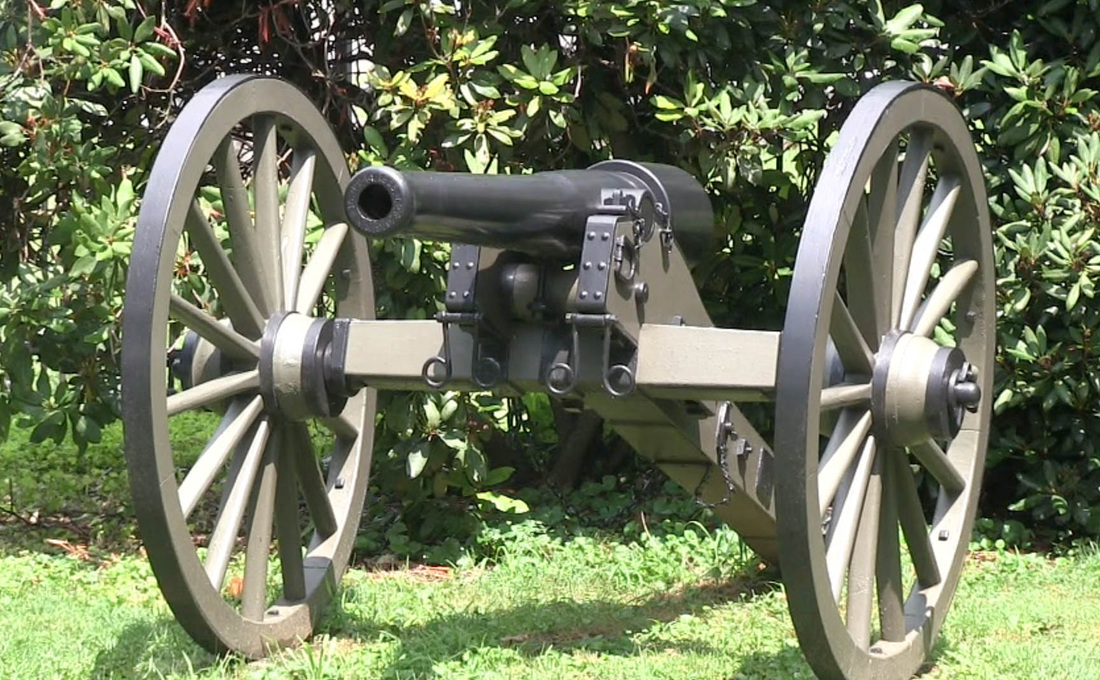

On the morning of July 1, 1863, Wheeler’s artillery battery was eleven miles from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, moving along at a deliberate pace, when a messenger arrived urging speed. The men flew toward the town, gun carriages rattling and bouncing over the stony road, food and kettles breaking loose from the caissons, and cannoneers running to keep up. When they reached Gettysburg, tens of thousands of men in gray and blue were gathering their forces in a vast pattern of artillery, infantry, and cavalry. Wheeler’s battery rushed from one point to another in this scene of noise, movement, and confusion. Hurrying through town, the soldiers passed ladies waving handkerchiefs and cheering them on and stopped at a place called Cemetery Hill, where the Union forces concentrated their artillery.

“Wheeler,” said another officer, “which are the rebels and which are our men?”

“You pays your money,” said Wheeler, “and you takes your choice.”

The Confederates were driven back, then and in other efforts to break the Union lines. Both armies rested on July 4, and the next day Lee began the dismal march back to Virginia. He had failed to win the northern victory that would have meant so much to his cause.

William Wheeler’s role at the Battle of Gettysburg was like that of hundreds of other junior officers. He stuck to his post, opposed the enemy advance, and kept up a strong fire. He was a minor actor in an epic drama. Yet he loved his role. “Somehow or other,” he told his friends at home, “I felt a joyous exaltation, a perfect indifference to circumstances, through the whole of that three days’ fight, and have seldom enjoyed three days more in my life.”

Strange words, perhaps, for a man who admired the classics, led prayer meetings, and established a camp school. But battle had become a way of life to Wheeler. Not that he was unaffected by suffering; in his mind he carried images of the devastation of war: trees speckled with bullets and bored through by shells; a fellow artillery officer killed when a shell plowed through his horse; an infantryman’s leg, blown off at Gettysburg, whirling “through the air like a stone, until it came against a caisson with a loud whack.” Worse still was the sight of his own men hospitalized with mortal wounds. One of the hardest to bear was a “fine-looking young Irishman, with a . . . deep susceptibility to both pain and pleasure,” whom Wheeler visited in the hospital. “One of his wounds had affected the nerves,” he wrote, “and the pain came in great wrenches and spasms that made him gnash his teeth and beat his feet on the bed in agony. I became so sick that I could hardly get to the door.”

Different men accommodated to battle in various ways. Some were armed with the giddy assurance that they could never be shot. Others refused to speculate about their prospective fortunes. Wheeler’s resolution came from another source—the certitude that he would be killed. In the first years of the war he had looked at the magnitude of the conflict and concluded that almost everyone who stayed in the army for the duration would die. He wrote home in 1861, “This is emphatically a war deadly to officers, and I have fully made up my mind never to see any of you again.” In the next year he predicted that “few of the army now in the field will ever see their homes again; the new conscripts will win the glory of finishing the war.” He disliked thinking about the possibility of survival, because such imaginings weakened his resolve. “I prefer to accept the belief that I must fall,” he wrote. “The question with us is not whether we shall die or not, but how we shall die and among what surroundings.”

As much as Wheeler enjoyed the craft of artilleryman, the war’s purpose excited him more than its process. He called himself an “extreme Emancipationist” determined to see the end of slavery. Men fought in the Civil War for many reasons: some because they were drafted, others for adventure, and others to save the Union. Wheeler and soldiers like him fought with the moral fervor of medieval knights on a crusade, their goal the eradication of slavery. The war, he told his mother, “has become the religion of very many of our lives, and those of us who think, and who did not enter the service for gain of military distinction, have come more and more to identify this cause for which we are fighting, with all of good and religion in our previous lives.” His hero was Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, whom he called “a steam engine in pantaloons.” He had no patience with men who gave sparingly for the cause and rejoiced when the timorous McClellan, a “softy warrior,” was dismissed from command. Disgusted at the news of draft riots in New York City, he proposed a simple solution: he would set up his battery at a place on Broadway he knew where “the balls would ricochet splendidly on the hard pavement.”

The Union cause simply must prevail. It was to him “the same that the quest of the Holy Grail was to Sir Galahad.” He would endeavor, like Tennyson’s Ulysses, “to strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield.” After Gettysburg he acknowledged that the war might last many years, but he and his fellows would endure. “I am, in this matter,” he said, “like St. Paul’s Charity, ready to bear, believe, hope, and endure all things for the cause, knowing that if we do, we also, like Charity, shall never fail.”

(You know you want to!)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed