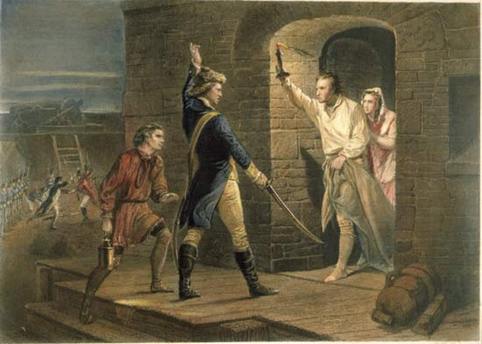

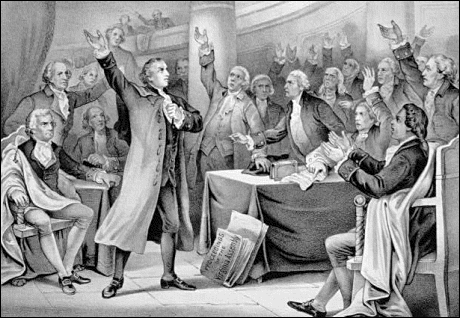

At dawn the Patriots brushed past the solitary soldier guarding the gate, and awed the sleepy Ticonderoga garrison without firing a shot. In one of the benchmark episodes of the Revolutionary War, Ethan Allen, leader of Vermont's "Green Mountain Boys," confronted British Lieutenant Jocelyn Felthan, demanding the surrender of the fort.

I've always loved this scene: there is Feltham, caught with his pants down -- literally, breaches in hand looking out at a crowd of American soldiers already inside his fort. An authoritarian British soldier, Feltham demanded better credentials than mere force. And the interesting thing is that Allen respected his demand. He could easily have said, "by the authority of cold steel and hot lead!" But like his British adversary, he embraced in a certain orderliness in politics. What to do?

Believing in natural rights, he could not say, like Monty Python in The Holy Grail, "The Lady of the Lake, her arm clad in the purest shimmering samite held aloft Excalibur from the bosom of the water, signifying by divine providence that I, Ethan Allen, am empowered to demand your surrender."

And so he offered up the "The Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress." And he added the phrase, "The authority of the Congress being very little known at this time." In other words, he might have simply claimed the power of Congress, but it being new, he reached into his pocket for a trump card, God!

The cannon at Ticonderoga would soon be on their way to Boston, carted along by a force led by Henry Knox, the future American Secretary of War. They would add "authority" to the American claim to Independence during the years ahead. And also the name of "the Great Jehovah" would be invoked often during the Revolution.

View more entries on the American Realities blog...

(You know you want to!)

This current post is one of a growing number of historically-themed entries on americanrealities.com. To see a complete list of other entries, click here

RSS Feed

RSS Feed