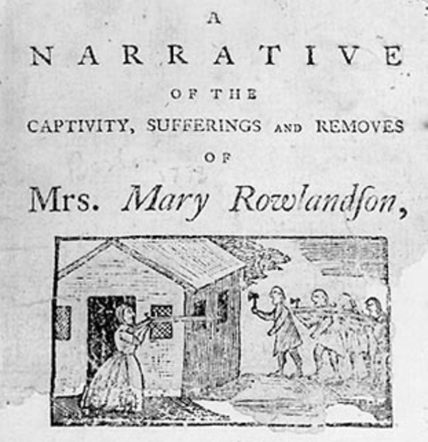

(See note below on the authenticity problem posed by this image.)

On the tenth of February 1675, came the Indians with great numbers upon Lancaster: their first coming was about sunrising; hearing the noise of some guns, we looked out; several houses were burning, and the smoke ascending to heaven, and There were five persons taken in one house, the father, the mother and a sucking child, they knocked on the head; the other two they took and carried away alive. There were two others, who being out of their garrison upon some occasion were set upon; one was knocked on the head, the other escaped; another there was who running along was shot and wounded, and fell down; he begged of them his life, promising them money (as they told me) but they would not hearken to him but knocked him in head, and stripped him naked, and split open his bowels. Another, seeing many of the Indians about his barn, ventured and went out, but was quickly shot down. There were three others belonging to the same garrison who were killed; the Indians getting up upon the roof of the barn, had advantage to shoot down upon them over their fortification. Thus these murderous wretches went on, burning, and destroying before them.

• Sheltered behind a hill and a barn they shot upon her house "so that the bullets seemed to fly like hail. "

• The Indians next set fire to the house in which she and other towns folk were seeking refuge. "Now is that dreadful hour come, Rowlandson writes, "that I have often heard of." They must die by fire in the house or rush outside and die by gun or spear.

Some in our house were fighting for their lives, others wallowing in their blood, the house on fire over our heads, and the bloody heathen ready to knock us on the head, if we stirred out. Now might we hear mothers and children crying out for themselves, and one another, "Lord, what shall we do?" Then I took my children (and one of my sisters', hers) to go forth and leave the house: but as soon as we came to the door and appeared, the Indians shot so thick that the bullets rattled against the house, as if one had taken an handful of stones and threw them, so that we were fain to give back.... But out we must go, the fire increasing, and coming along behind us, roaring, and the Indians gaping before us with their guns, spears, and hatchets to devour us.

Mary Rowlandson reports that in the past, when thinking of captivity, she had thought, "I should chose rather to be killed by them than taken alive." But the "glittering weapons so daunted my spirit," she writes, "that I chose to go along with those (as I may say, ravenous beasts." More than a dozen of her neighbors lay bleeding on the ground "like a company of Sheep torn by Wolves." Rather than lie among them, she chose to take her wounded child and follow obediently into captivity. During the next two weeks her Indian captors carried her by twenty "removes" from one campsite to another, as English soldiers mounted ineffective campaigns to conquer the Indians. Finally, after enduring fatigue, hunger, cold , the death of her injured "babe," she was ransomed and regained her freedom.

A few years later she wrote a book about the event, in order, as she said, "that I may better declare what happened to me during that grievous Captivity." The book was an immediate best seller in colonial New England and remained one of the most popular books in early America. It tells in vivid detail about a series events in the New England wilderness, and it also provides abundant information about the customs of her Indian captors.

Of the many books I have taught in my university courses, Mary Rowlandson's Narrative is one of my favorite -- despite the fact, or perhaps because questions exist about the authenticity of the book. Scholar's (and students) ask, can we trust a description of the Indians that is filtered through the lens of Puritan prejudice? Could Rowlandson actually remember all the details that she supplies in the book? Did the ministers who likely assisted her in developing the narrative for publication -- did they coax her to write it in a way to serve their religious and cultural sensibilities? We know that the image on the 1773 edition of the book (which was first published in 1682) falsely shows Mary with a gun. She can hardly be blamed , however, for that image, which was published long after her death. But were there other errors in her account for which she was consciously or unconsciously responsible?

Classroom Detective Work: The Mary Rowlandson "Lesson Plan"

One of my favorite moments in teaching Rowlandson's Narrative came in a class where several students in succession castigated her for her critical attitude toward the Indians. They argued that from the beginning she showed her prejudice by referring to the Indians as "wolves" and "beasts." After listening patiently, one student said, "You know, she had just lost her sister and many friends, she was injured, and she was carrying her wounded child. She was having a bad day."

Very true!

Of course, there is a larger question than whether or not Mary Rowlandson was justified in her hostility to the Indians -- an attitude which, by the way, she did moderate sometimes during her ordeal. But the real question is whether we can trust the information she presents about Indian behavior and practices while she was a captive. Did she, intentionally or not, twist the facts?

I was preparing to discuss Rowlandson in tomorrow's graduate class when Clio, the god of history, provided one those strokes of good fortune that sometimes enrich the historian's craft, I was listening to a TED talk and happened unexpectedly on two excellent prompts for our discussion of Rowlandson's narrative.

1) The first is from a talk by Scott Fraser, who is billed on TED as "a forensic psychologist who thinks deeply about the fallability of human memory." He describes a case where five witnesses incorrectly identified a drive-by shooter, resulting in the man's wrongful incarceration for murder. In Fraser's talk, "Why eyewitnesses get it wrong," he describes how concrete conditions, such as poor lighting, and our own imperfect memories lead us to "get it wrong" when we try to remember the details of a traumatic episode. "The brain abhors a vacuum," he says. It "fills in information that was not there." Amplifying this point Scott argues, "All our memories are reconstructed memories. They are the product of what we originally experience and everything that's happened afterwards."

-- Applying these observations to Mary Rowlandson's captivity, my students and I will be asking whether there is any evidence that in her "reconstructed memories" she did indeed fill in information about her captivity "that was not there" during the real adventure.

2) The second TED talk, "The Fiction of Memory," dovetails nicely with the first. Presenter Elizabeth Loftus, a psychologist who studies memory, is interested, like Scott Fraser, in the "fallability of human memory." But she focuses not so much on the brain's own weakness as on the ways that others can influence someone's memory. As a result of "memory-manipulation" people can be made to remember things that did not happen or remember them "differently from the way they really were." Loftus like Fraser describes a criminal case where inaccurate memories, in this case "implanted memories" led to the conviction of an innocent man.

-- As we analyze Mary Rowlandson's account of her captivity, we will be considering the possibility that some of the narrative may bear the marks of descriptions or conclusions that may have been implanted by friends and advisors after her "redemption" from the Indians.

Tomorrow my students and I will be embarking on a journey to explore of events that happened 338 years ago and that continue to tease our memories even today.

I'll be reporting on our explorations in a few days.

In the mean time:

1) if you would like to read Mary Rowlandson's Narritive I suggest going to the Project Gutenberg eBook site to see the full text, except for the introduction.

2) To view Scott Fraser's TED talk, click on this title: "Why eyewitnesses get it wrong."

3) To see Elizabeth Loftus's TED talk, click on this title: "The Fiction of Memory."

4) To learn more about TED talks, in general, go to the home page here.

By the way there are now more than 1500 TED talks on line, and the TED stands for Technology, Entertainment, and Design. I just learned that myself.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed